Inside the Collections

Specimens that span Earth’s history combine wonder with scientific worth

Impressive specimens abound in the collections of the Jackson School of Geosciences. There’s the Texas Pterosaur, Quetzalcoatlus, the largest flying animal ever discovered; the rock cores that first hinted at the amazing energy productivity of the Eagle Ford Shale; and a trove of jewels personally faceted by internationally recognized lapidarists Glenn and Martha Vargas.

These select notables are just a miniscule sample of the millions of items kept

inside the collections, which include:

- The Jackson School Museum of Earth History’s Vertebrate Paleontology Collections, which hold approximately 2 million specimens and is one of the largest collection of vertebrate fossils in the United States.

- The museum’s Non-Vertebrate Paleontology Collections, The sixth largest non-vertebrate fossil collection in the United States. The collections hold an estimated 4 million specimens, which include rocks and minerals along with fossils. Roughly 95 percent of Texas’ 254 counties are represented among its diverse fossil holdings.

- The Bureau of Economic Geology’s three core and cuttings repositories — spread across Austin, Houston and Midland — which have combined holdings of nearly 2 million boxes of geologic material, and make the repositories among the largest public collections in the world.

- And the Jackson School’s gem and mineral collections, which hold hundreds of thousands of minerals and gems — from expertly faceted jewels, to historic samples collected during the early mapping of Texas, to meteorites.

Through careful curation and cataloging, the immense array of material is a world-class resource for education and research. The collections’ designation as a public resource means that students, scientists and the general public alike are able to benefit from the rare and diverse materials stored within them. A small sampling from across the collections is featured on the following pages. Chosen for their intrigue and beauty — as well as their scientific importance — we hope these treasures spark your curiosity while showcasing the importance of maintaining collections that catalogue the history of our planet.

Jackson School Museum of Earth History: Vertebrate Paleontology

TOP LEFT: Texas Pterosaur, Quetzalcoatlus northropi | Big Bend national park, Texas

With an estimated wingspan of 36 feet, the Texas Pterosaur is the largest known flying animal to have ever lived. The species lived during the late cretaceous and was discovered in 1971 by Douglas Lawson, a UT geology graduate student. Photographer Sarah Wilson for scale.

TOP RIGHT: Scimitar-Tooth Cat, Hometherium Serum | Friesenhahn Cave, Bexar county, Texas

This big cat lived in Texas 2 million to 20,000 years ago and has been found in several caves in the Hill Country. The saber teeth are 3 inches long and have serrated edges on both sides.

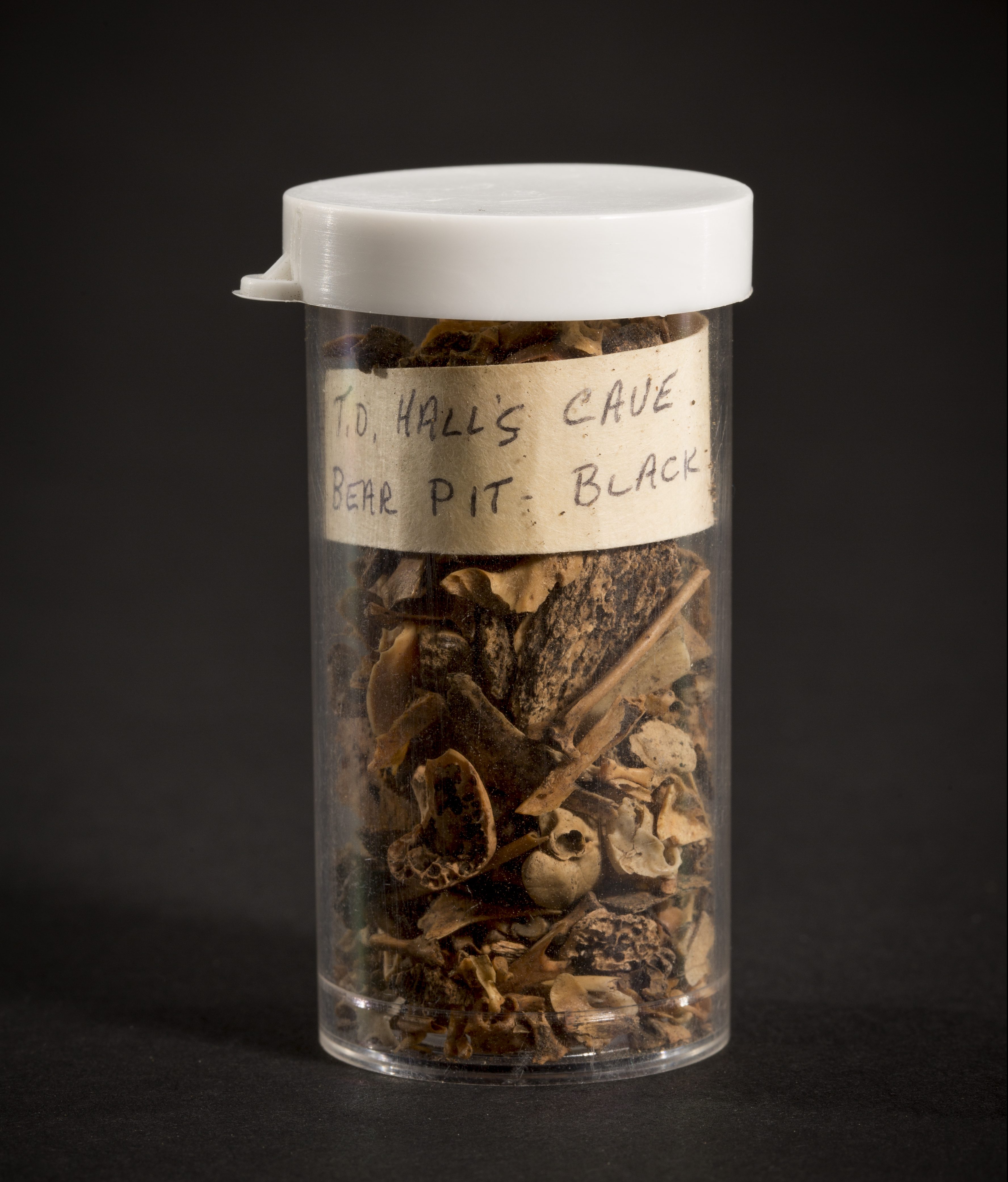

BOTTOM LEFT: Unsorted skeletal remains | Hall’s Cave, Kerr county, Texas

These batch-curated bones representing numerous species found in cave sediments are stored in bulk until needed for research. They will be sorted, identified, and curated, and can be used in biodiversity, climate, DNA, and radiocarbon dating studies

BOTTOM MIDDLE: Alligator snapping turtle, Macrochelys temminckii | Hidalgo Falls, Washington county, Texas

One of the largest alligator snapping turtles known at the time it was collected, this skull was excavated during dredge operations in the Brazos river and described in a 1911 publication by O.P. Hay.

BOTTOM RIGHT: Dire wolf, Canis Dirus | Rancho la Brea, Los Angeles, California

The world famous la Brea tar pits preserve millions of fossils that lived between 11,000 and 50,000 years ago. Stained deep brown by the natural asphalt that trapped the animals, these specimens are similar to the flora and fauna that lived in central Texas during the Pleistocene.

Jackson School Museum of Earth History: Non-Vertebrate Paleontology

CLOCKWISE:

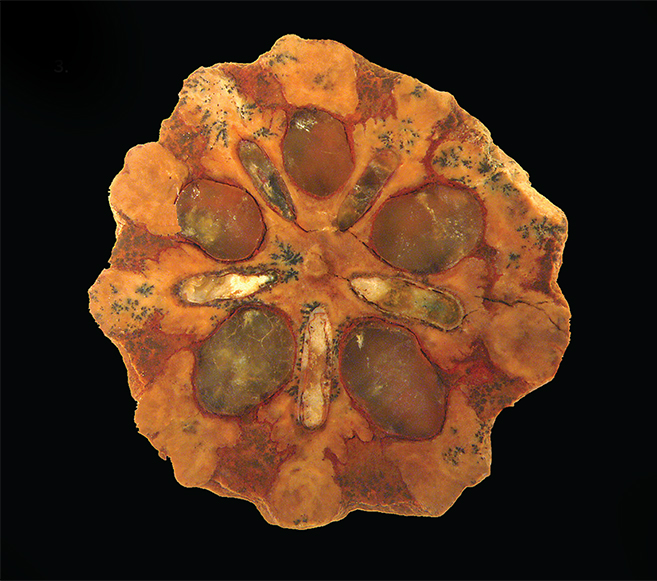

1. Devonian sea urchin, Archaeocidaris brownwoodensis | Texas, Winchell formation

A sea urchin’s mouth is normally hidden inside its shell. In this fossilized specimen, the shell fell apart and exposed the star-shaped top of the mouth, an apparatus is called aristotle’s lantern.

2. Brachiopod with markings, Dictyoclostus welleri |Callahan county, Texas

Brachiopods are considered to be living fossils, and although uncommon today, were some of the most common shellfish during the Paleozoic era. The light colored chips in the fossil were made by barnacles that bored through the shell. The concentric black rings are from a paleontologist’s grease pencil.

3. Paleogene bivalve, Venericardia alticostata | Burleson county, Texas

This specimen was collected more than a century ago by the bureau of economic geology during a geologic survey of Texas in 1899. The red mark designates the specimen as a holotype, the specimen on which the species description is based.

4. Cretaceous oyster, Ilymatogyra arietina | Del Rio formation, Texas

The distinctive spiral shape of this oyster’s shell has earned it the nickname “ram’s horn oyster.” The species is a common find in fossil locales around Austin.

5. Paleogene oyster, Cubitostrea sellaeformis | Cook mountain formation, texas

The tissue-paper appearance of this oyster’s shell relates back to the specimen’s life history. As the animal grew so did its shell, with the old layers stacking atop the new. The grooves in the shell represent times when the oyster did not have adequate resources to enlarge its home.

6. Cross section of fruit pit, Dracontomelon macdonaldii |Los santos state, panama, búcaro formation

This fossilized fruit pit was found in central america, but its only known living relatives grow in southeast Asia. Scientists are still working on what side of the world the fruit genus originated.

BOTTOM LEFT: Crinoid calyx and arms, Eopinnacrinus pinnulatus | Bromide formation, Oklahoma

This species of crinoid, or sea lily, lived during the Ordovician period when much of what is now the southern united states was under water. This example is a holotype, the specimen on which the species description is based.

Austin Core Research Center

TOP LEFT: Cuttings from Phillips Petro Co. No.1 |Lasalle county, Texas

The beginning of the eagle ford shale boom can be traced back these inconspicuous cuttings. First brought to surface by phillips petroleum in 1952, the cuttings laid in storage for decades until corpus christi geologist gregg robertson tracked them down in 2008 to ground-truth drilling plans by petrohawk energy corp. The eagle ford is now one of the most productive shale plays in the word, holding an estimated 8.5 billion barrels of oil.

TOP CENTER: Sandstone core from Gas Research Institute’s staged field experiment No.2 | Travis peak formation, Nacogdoches, Texas

Open natural fractures abound in this piece of sandstone core collected from 9,842 feet in the cretaceous travis peak formation, an important low-permeability gas reservoir in east texas. Fractures like these serve as important conduits and controls for gas extracted from low-permeability reservoirs.

TOP RIGHT: Tenneco No. 1 Ney Well | Pearsall Formation, Texas

The sediments that comprise this eighteen feet of core from the lower Cretaceous Bexar member of the pearsall formation were deposited in shallow and quiet water where burrowing organisms and oysters could easily thrive. The yellow section represents later geochemical alteration, indicating a time when oxygenated water was flowing through the rock. Equivalent organic-rich strata downdip make the Bexar member an active exploration target for unconventional oil and gas

BOTTOM LEFT: Tenneco No. 1 Ney Well Core Slab | Sligo formation, South Texas

The Sligo formation is known for zones of porous limestone, which comprise a large portion of oil and gas production in north Louisiana, Arkansas and east Texas. This piece of core shows a fracture with cement fill and large pores. Fractures such as these can be a major conduit for hydrocarbon production.

BOTTOM CENTER: Arco No. 17 Griffin Core | Rusk county, Texas

The lightly colored upper cretaceous Austin chalk (bottom two rows), overlies sandstone and siltstone beds of the woodbine group that were deposited in a deltaic setting. The woodbine group has produced more than 5.4 billion barrels of oil in east Texas since the field’s discovery in 1930.

BOTTOM RIGHT: Core of pure salt | Midland basin, West Texas

This nearly transparent, Permian salt core was sampled from a well in west Texas in the 1980s. The work was part of a department of energy-funded project that tasked the bureau of economic geology with evaluating bedded salt layers to see if they could serve as storage for high-level radioactive waste. Yucca mountain in Nevada was ultimately chosen over Texas.

The Vargas Collections, The E.M. Barron Collections

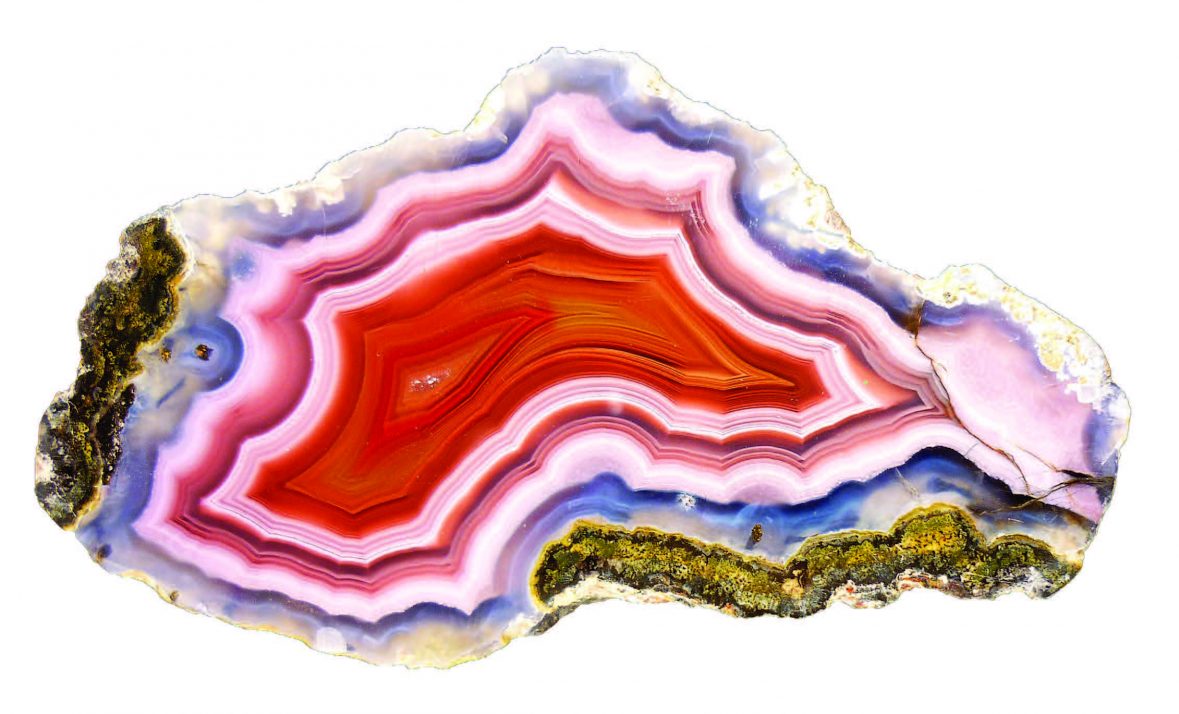

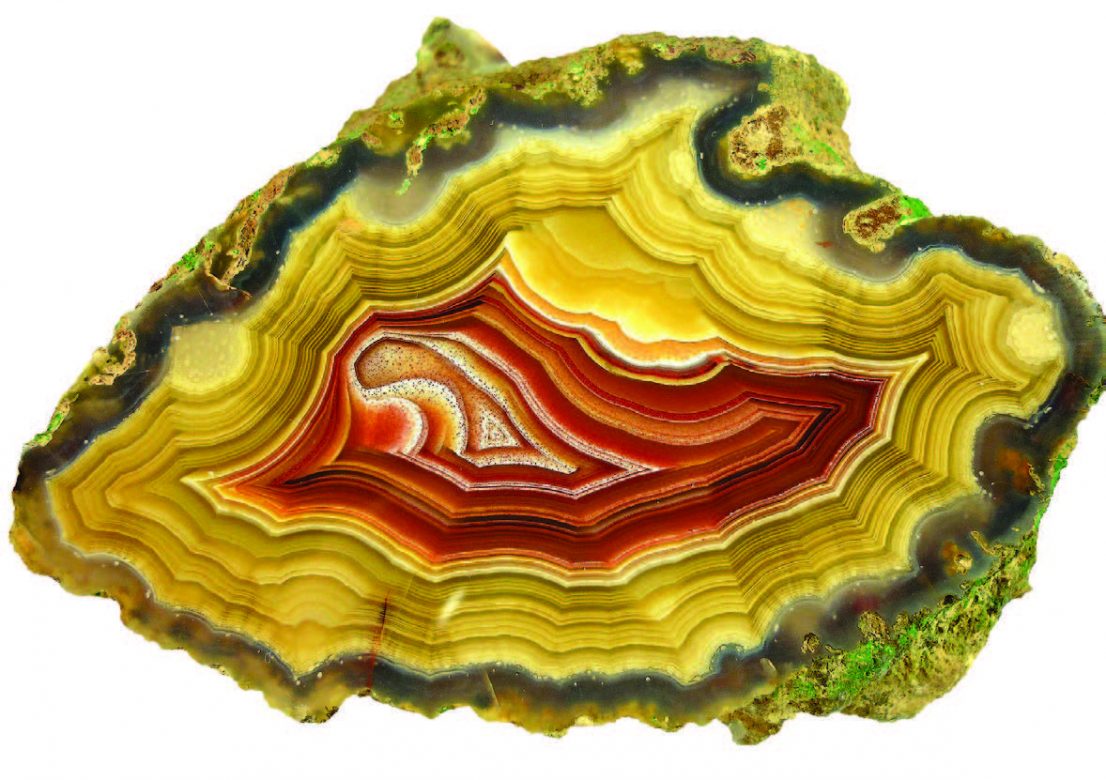

TOP LEFT, RIGHT & BOTTOM CENTER: Agates | Laguna ranch Chihuahua, Mexico

These three specimens are part of the more than 500 agates held by the Barron collection, which was donated to the university by colonel Elbert Macby Barron. The agates are the jewel of the collection. They are among the best specimens of their kind and showcase the spectacular array of colors that make agates from northern Mexico among the most prized in the world.

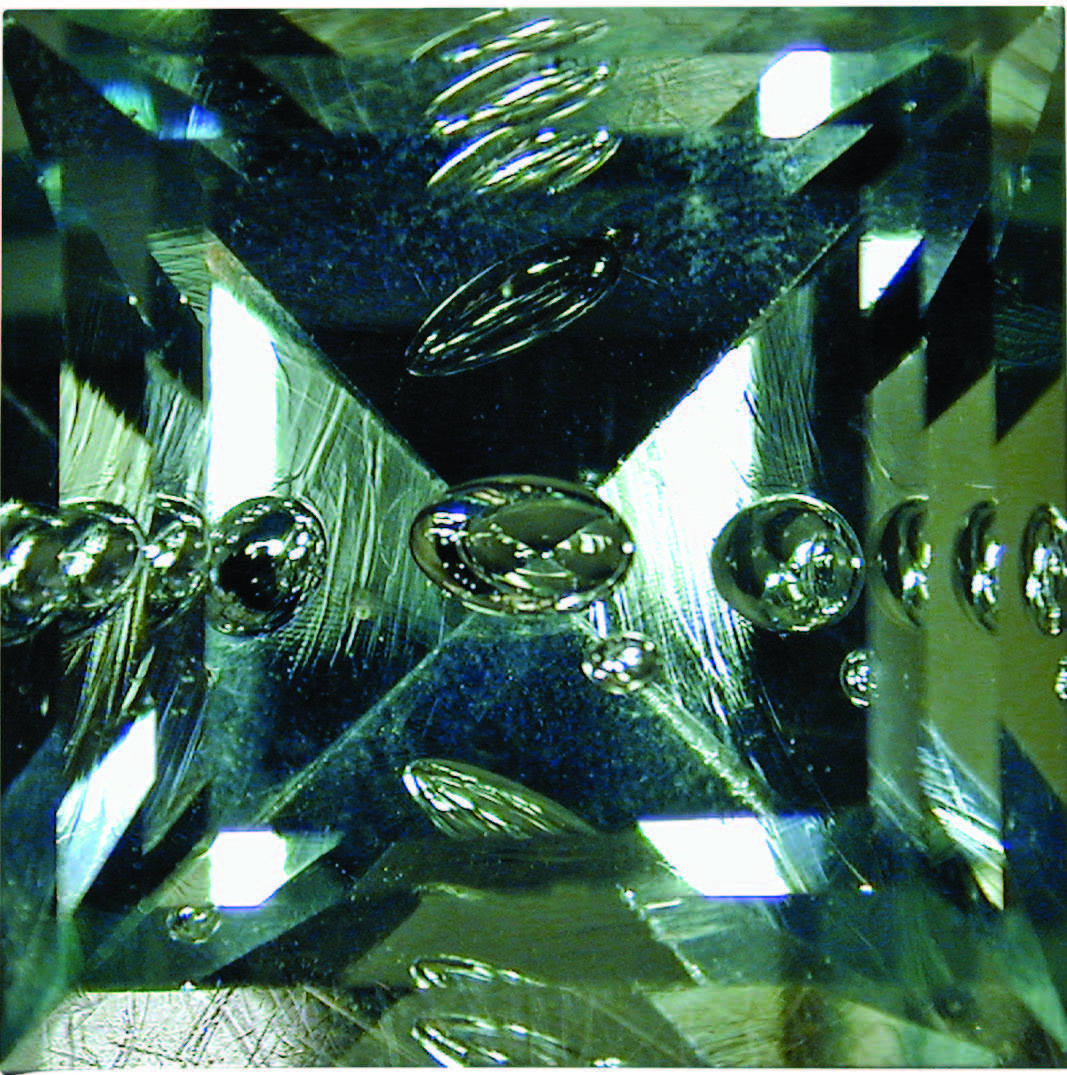

TOP CENTER: Green glass with bubble, round mixed cut | unknown

BOTTOM LEFT: Quartz, variety Ametrine, oval brilliant cut | Brazil

BOTTOM RIGHT: Quartz, variety citrine, pentagonal step cut |unknown

The three gemstones are among the more than 1,000 faceted gemstones displayed in hand-made wire mounts that make up the Vargas Gem and Mineral Collection. Glenn and Martha Vargas assembled the collection over 60 years, hand-selecting and faceting the stones themselves. For 24 years, they taught their craft to the thousands of students who took their gems and gem minerals course in the Department of Geological Sciences

The University of Texas at Austin

Web Privacy | Web Accessibility Policy | Adobe Reader