Energy, Discipline And Vision

For nearly six decades, Bill Fisher has been a driving force in geology in Texas and beyond, helping turn the Bureau of Economic Geology into a world-class research institution, launching the Jackson School of Geosciences, educating generations of geosciences leaders and shaping policy across the nation.

BY ANTON CAPUTO

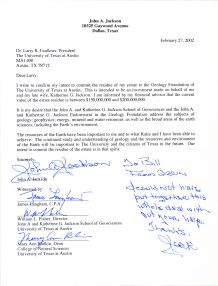

Among the books, memorabilia and pictures that line the walls and shelves of Bill Fisher’s office, a typed letter hangs near the desk. At the bottom are signatures and a note scribbled firmly in the right corner. It reads:

To Bill, from Jack,

I could not have put together this whole

deal without your help.

Thanks,

Jack

That simple message from Jackson School of Geosciences founder Jack Jackson succinctly sums up the fundamental role Fisher had in the formation of the Jackson School — without him, there probably wouldn’t be a school.

This fall, Fisher is retiring after nearly six decades with The University of Texas at Austin. During that time, he led the Bureau of Economic Geology for 24 years, growing it from a small, well-respected shop into a national and international powerhouse. He made foundational scientific breakthroughs in sedimentary geology that helped him earn a place in the National Academy of Engineering and win just about every major award a geoscientist can receive. He made stops to serve in Washington, advising presidents and Congress on national energy and science policy. He supervised or co-supervised 155 graduate students and taught hundreds more in Texas and beyond. And, of course, there was the relationship Fisher fostered with Jackson and stoked over the years, along with a small group of others, that would lead to the formation of the Jackson School and ultimately help change the face of geosciences in Texas.

“Bill was the thread of continuity through it all,” remembered Larry Faulkner, who served as university president when the Jackson gift that enabled the formation of the school was finalized. “Bill and Jack had a personal

relationship that went back a long way, and long-established relationships were important to Jack.”

By the time the ink dried in 2002 on the letter officially bequeathing the Jackson Estate to The University

of Texas, Fisher had known Jackson for 27 years. Their first meeting dated back to when Jackson joined the Geology Foundation in 1975, but the relationship really strengthened in the decade before his 2003 death as Jackson hinted at his desire to do something meaningful for his beloved university. It was a relationship Fisher prioritized while juggling roles as bureau director, department chair, Geology Foundation director, president of national societies and many more duties.

Why? Well of course, he liked Jackson. But ultimately it boiled down to a singular skill that anyone who has spent significant time with Fisher is quick to point out: Fisher sees the big picture and recognizes opportunities. It’s a skill he would exhibit time and time again during his long, storied career. In the case of Jack Jackson, he saw the opportunity to help a friend leave a positive, permanent impact on the geosciences while building what would become one of the world’s best geosciences programs in the process.

“If you’re willing to spend some energy, and if you’re willing sometimes to take a little bit of a chance, it can

make all the difference in the world,” Fisher said.

Making the Grade

Faulkner sums up the impact of Fisher’s career succinctly.

“Bill is as influential a figure in geology in Texas as anybody ever has been,” he said.

But for someone who would have so much influence on Texas geology, Fisher started out life with virtually no connection to the state or the discipline.

Born in tough southern Illinois coal country during the Great Depression, Fisher grew up on the farms where his father worked, attending first a one-room and then a two-room school house. He worked his first full-time summer job at age 8, receiving 50 cents a day to punch wire in a hay bailing operation. At 11, he graduated to driving the tractor that pulled the bailer. By the time he graduated from high school, Fisher, like most kids of his generation, was well acquainted with hard work.

Fisher was a bright and diligent student, and his parents encouraged him to pursue college even though they had not, reasoning that earning a living with your mind is preferable to earning one with your back. After years working on the farm, he wasn’t hard to persuade. Fisher earned a scholarship to the University of Illinois- Urbana-Champaign, but he found it less expensive to attend Southern Illinois University without a scholarship than the University of Illinois with one. He started as an agriculture major but soon switched to biochemistry. Not long after making the switch, one of his professors told him he wasn’t cut out for chemistry and suggested he switch to geology, which the professor himself was doing. Fisher was disappointed with his professor’s take on his chemistry skills, but obviously the change suited him.

“I liked it and stayed with it,” he said. “If you find something that you like to do and is fun to do, it’s the best way to make a living.”

After receiving his undergraduate degree and marrying Marilee Booth, whom he met at church when he was a boy, Fisher was looking forward to beginning his graduate studies at the University of Kansas. But the U.S. government had other ideas. In 1954, Fisher was drafted and sent to South Korea for almost two years. He managed to wrangle a position in a

petroleum laboratory by exaggerating his background in chemistry. The lab was preferable to his initial position at the front, but Fisher still found himself counting the days until he could return to his wife and pursue his career.

Still, Fisher said he came away with a valuable life lesson.

“You learn how to tolerate a system that you are in that you can’t do a damn thing about,” he said. “Over life’s course, you occasionally get into situations where you don’t have much control. You

learn to work through the situation the best you can.”

"If you find something that you like to do and is fun to do, it's the best way to make a living."

– William Fisher

After returning home, Fisher attended the University of Kansas as he planned. He was drawn there by the presence of Professor Raymond C. Moore, one of the most famous geologists of his time and a larger-than-life character in the field. Moore had a reputation for terrorizing students, particularly if he felt they were not pulling their weight. He was known on more than one occasion to dump a thesis into the trash in front of a panicked grad student, leaving the student to sift through the garbage to retrieve it after Moore had left for the day. Here again, Fisher learned another lesson that would serve him well

“You learn to be prepared,” said Fisher, whose Ph.D. thesis explored the geology of the western Grand Canyon at Moore’s directive. “If you weren’t, he would just run you right out. He would say, ‘Don’t waste my time.’”

When Fisher graduated with his Ph.D. in 1960, jobs in the industry were hard to find, but he managed to get three job offers: Texaco, in Farmington, New Mexico; Narragansett Marine Laboratory at the University of Rhode Island; and the Texas Bureau of Economic Geology in Austin. Fisher visited Rhode Island but was put off by the high cost of living and the specter of harsh winters. Moore urged him to consider the research position at the bureau. The advice set his course — and that of the bureau, as well.

Capital To Capital

When Fisher joined in 1960, the bureau was a well-regarded but small organization. It was in an area known as the Little Campus near Scholz Garten, the famous beer garden that a young Fisher and his colleagues would frequent. Fisher was hired as a coastal plain stratigrapher despite the fact that the job had little to do with the work he conducted to earn his Ph.D.

It was in his early years at the bureau that Fisher formed what would be a lifelong friendship with then bureau director Peter Flawn, who would become a mentor throughout Fisher’s career. Flawn, who would later become president of UT Austin, named Fisher associate director of the bureau in 1968 and then acting director in 1970 when Flawn became the university’s acting vice president of academic affairs. Six months later, the university pulled the acting from Flawn’s title, and Flawn pulled the acting from Fisher’s.

There have been only eight directors in the organization’s history. Fisher was the longest serving, taking the position in 1970 and stepping down in 1994. As director for 24 years, Fisher was at the helm for almost a quarter of its existence.

Current bureau Director Scott Tinker, who has served in the role for 19 years, said it’s difficult to overstate the importance of Fisher’s tenure at the bureau in terms of widening its scope and profile.

“The bureau had its first real big growth spurt under Bill’s leadership, and its hiring expanded beyond the Texas border quite a bit,” he said. “I think Bill believes that you are only limited by your own ambition, and so nothing is really off the table.”

The raw numbers back this up. In 1970, Fisher inherited an organization with a budget of $384,000. That grew to more than $20 million by the early ’90s. That tremendous growth was achieved by expanding the mission and the vision of the bureau. When Fisher came, the bureau relied on, as it always had, the relatively modest line-item funding the Texas Legislature granted it for serving as the state’s geological survey. By the time he left the role of director, more than 90 percent of its funding came from grants and contracts. That remains the case to this day.

The funding has enabled the bureau to take part in a diverse array of research. When Fisher first became director of the bureau, he continued work on the environmental atlas of the Texas coast that he started on as a researcher. Fisher also oversaw the bureau as it stepped up its efforts on basin analysis and depositional system work on the coastal zone and the Permian Basin. In 1972, Fisher persuaded the Texas Water Development Board to fund a study of the environmental geology of South Texas in concert with its plans to develop new reservoirs. Then in 1973, the OPEC embargo created oil shortages and sent gasoline prices through the roof, creating interest in alternative energy sources. This provided the

bureau with the opportunity to expand research into geothermal, lignite and uranium resources.

“Those were times when energy resources were getting scarce and environmental concerns were big,” he remembers. “It was a question of: Can you catch that wind? The answer was, yes you can, but you’ve got to know how to do it.”

In 1975, Fisher was offered a position at the Department of the Interior in Washington, D.C., as deputy assistant secretary for energy. Fisher was no stranger to offering his expertise on a national level, having served on the boards of national organizations and policy advisory councils. He knew such a position could expand his knowledge and career. However, he was hesitant because of the financial and personal difficulties posed by moving his young family to Washington. He might have decided against the move, but his spouse Marilee insisted he take the job. Fisher took a temporary leave from the bureau, naming Associate Director Chip Groat acting director in his absence. Later

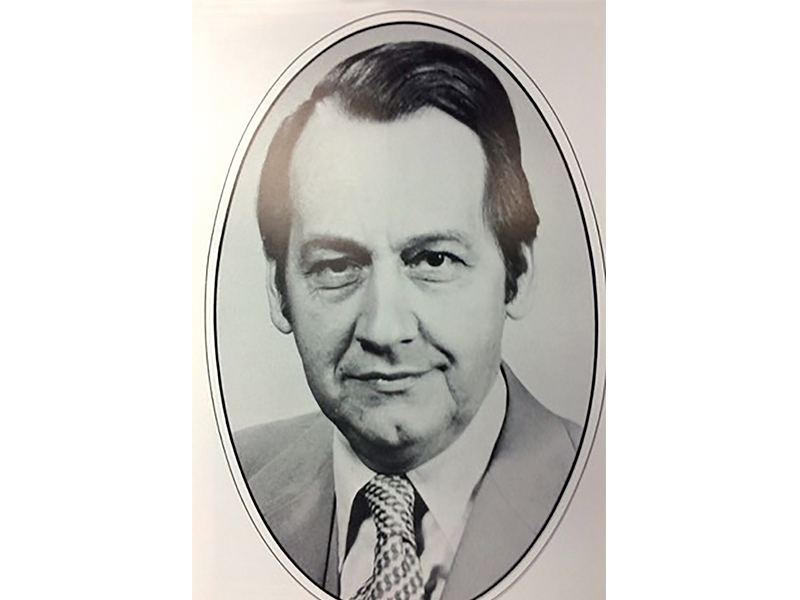

that year, he was appointed assistant secretary of energy and minerals by President Gerald Ford.

Fisher describes his time in Washington as a fast-paced and sometimes grueling environment. But he said it honed his ability to learn quickly, prioritize and figure out whom to trust while delegating duties. It also expanded his view of what the bureau could do when he came back to the helm of the organization in 1977. For example, when he returned, Fisher helped the bureau become involved in scientific studies for the national efforts to store both high level and low-level nuclear waste in West Texas among many other new avenues of research including the quickly evolving world of oil and gas recovery.

Even after his return to Austin, Fisher would be a frequent visitor to Washington, serving on advisory committees and presenting testimony to Congress. All told, he has presented testimony on more than 100 occasions to the U.S. Congress and Texas Legislature. He also served on the White House Science Council under President Ronald Reagan.

Leadership in Action

Fisher recognized that generating world-class research at the bureau meant creating the right environment. As director, he played a large part in setting up a workplace where science could thrive.

Among Fisher’s innovations at the bureau was starting the industrial associates programs, which were the first at the bureau and among the first in the country when the Offshore State Lands Lab (1985), the Reservoir Characterization Research Lab (1986) and the Applied Geodynamics Lab (1988) were launched. These programs bring industry together into a consortium to help fund bureauled research. Each industrial partner provides a relatively small amount of funding, but the combination is enough to support substantial research that

benefits all the partners.

There was a time when industry simply didn’t fund academic research, explained Tinker. Each company depended on its own labs, but this became an issue in the 1980s as the industry took a downturn and research funding began to dry up. Fisher saw an opportunity for the bureau to step into the void, and the industrial associates programs were born.

The approach has since been emulated across the country, including, as Tinker points out, by successive directors of the bureau. There were four industrial associates programs at the bureau when Tinker took over in 2000. There are currently 11.

“That’s the kind of vision Bill has,” Tinker said. “It’s a matter of looking beyond today and looking over the long term. He’s been a great mentor in that way.”

Jackson School Dean Sharon Mosher, who started at UT Austin as an assistant professor in 1978 before being named department chair in 2007 and dean in 2009, said Fisher has been a constant source of support.

“I’ve learned a great deal from Bill about leadership over the years, and I have regularly sought his advice on any number of issues,” she said. “Bill has been a tremendous resource and has always been willing to help. I feel fortunate that I’ve had the opportunity to work with him and hope that he remains available after his much deserved retirement.”

Fisher was also adept at juggling tasks, even big ones. In 1984, he was named chair of the Department of Geological Sciences, taking on the role at the same time he was bureau director and chair of the Geology Foundation. Professor Mark Cloos, the Getty Oil Company Centennial Chair in Geological Sciences, worked closely with Fisher during much of his time at the department, acting as associate chair under Fisher from 1986 to 1989 and then serving as department chair himself from 1996 to 2000, when Fisher was chair of the Geology Foundation and a professor.

Cloos remembers Fisher taking over at a difficult time when enrollment was falling quickly because of a downturn in the oil and gas industry. Fisher’s business and leadership skills proved to be crucial as he brought a steadying hand to the department, Cloos said. He even helped create new courses aimed at nonmajors to help keep enrollment up.

“He helped bring a sense of order and direction,” Cloos said. “That was fundamentally important.”

Doug Ratcliff worked with Fisher for most of his career, starting as a clerk in the bureau’s core repository before Fisher recognized his talent with numbers and brought him over to help with the bureau’s budgeting.

“He’s the best numbers guy alive,” Fisher said, pointing out that Ratcliff had to keep track of more than 200 contracts at a time for the bureau at some points.

Fisher also took him over to the dean’s office when the Jackson School was formed to help with the enormous task of documenting the Jackson gift — valued at $272 million when it was finalized — and figuring how to use the money to tie the bureau, the Department of Geological Sciences and the Institute for Geophysics into the Jackson School.

Fisher was a tough and driven boss, Ratcliff remembers, but he got the best out of people.

“He was an incredible mentor, and he backed it up,” Ratcliff said. “He demanded a lot from his scientists. He demanded they do what was required by the contract, and in addition, use

their ingenuity and a lot of hard work to generate publishable, meaningful scientific results.”

Understanding that publishing worldclass science — not just conducting it — was the lifeblood of an organization like the bureau, Fisher set up a complete editing and graphics department to make it as easy as possible to create quality copy and figures for publication, a setup that Ratcliff said was unique at the time. Ratcliff also said that Fisher set up a rigorous internal peer review system and made everyone understand that they weren’t publishing solely for themselves, but were publishing for the bureau. It was part of a concerted effort to raise awareness of the organization and its science.

During his tenure as director, the bureau published 483 reports, maps and atlases, and 1,433 research articles. In addition, bureau staff members, taking an example from their energetic and outgoing leader, gave 2,828 invited lectures, served on 170 committees and served in 10 national offices of professional societies.

Groat, who is now a professor at Louisiana State University and acting director of that state’s geological survey, said that there is an important lesson to learn from all the activity.

“We need to be trusted in what we do well, but part of that is rooted in getting out there and communicating, and Bill symbolizes it well,” Groat said. “That’s something we all need to think about.”

Fisher’s good eye for talent and tremendous ability to see how smaller parts fit into a bigger plan often led to scientists being assigned tasks that didn’t fit in directly with their specialty, remembers Department Chair Charlie Kerans, who joined the bureau in 1985 as a research associate.

“He would say here is where you’re going, and here’s the big picture and how you fit into it,” he said. “That’s not the traditional approach, but that was his style.”

This certainly posed challenges to researchers, particularly if they weren’t versatile or open to change. But it also helped many grow and forge successful careers in areas they might not have considered. The best example, according to Kerans, is the late Martin Jackson, who came from South Africa to the bureau with an interest in working on brittle deformation. The work didn’t fit in with the opportunities available to the bureau at the time, so Fisher assigned him to salt dome research to help with potential geothermal projects.

“That was the start of the best-known salt tectonics person in the world,” Kerans said.

It was this type of foresight that helped Fisher years later to forge a strong relationship with Jack Jackson. The former oil and gas man, as Fisher pointed out, was a tough businessman and over the years reminded Fisher often that he could change his mind about the gift at any time.

“It was really just about getting on with him and developing trust,” Fisher said. “That’s true anytime, anywhere,

but particularly of individuals you are working with. You have to develop trust.”

As department chair for several years, Cloos remembers Fisher had great support from Marilee, who acted quietly as the “first lady” of the Geology Foundation. From the late ’80s to the late ’90s, she hosted the Geology Foundation Advisory Council for dinners, first at the Fisher home and later at their Hill Country ranch in Liberty Hill. She prepared a wonderful meal for a group that could approach 80 people. How the Fishers made room for everyone in the Austin house was memorable for all who attended. Cloos said Marilee probably hosted a dozen of these homey gatherings that created a truly special kind of interaction between the faculty and the department’s supporters who made up the advisory council.

Jackson attended many of these dinners. Through it all, the potential game-changing gift was not common knowledge.

“Very few people knew about it,” Cloos said. “Bill nurtured it along for more than a decade. And then it finally happened, and everything changed.”

Scientist and Educator

When reviewing Fisher’s many accomplishments as a leader and administrator, it could be easy to assume that running organizations took up all of his time. But he managed to do some teaching and conduct groundbreaking research.

Fisher’s research has focused on the areas of stratigraphy, sedimentology, and oil and gas assessment. He’s credited with two foundational discoveries. In 1967, he and colleague Joe McGowen introduced the concept of depositional systems, a fundamental part of modern stratigraphy and sedimentology. The second was the concept of systems tracts, introduced by Fisher and colleague Frank Brown, which linked contemporaneous depositional systems from source to sink. Among his other research highlights is a 1987 assessment he led for the Department of Energy that turned around the then prevalent view of natural gas scarcity.

Fisher was also a pioneer in the field of seismic stratigraphy, which was developed in the late 1960s and early 1970s simultaneously by Exxon researchers and Fisher, who was working with colleagues at the Petrobras Brazilian oil corporation, and later with Brown, to independently develop the approach in the offshore sedimentary basins of Brazil.

The first reference in scientific literature to the term seismic stratigraphy (actually “estratifia sismica” in Portuguese) was in

a paper published by Fisher and Brazilian colleagues Ercilio Gama and Hideberto Ojeda in the Bulletin of the Brazilian

Geological Society.

In recent years, Fisher has taken on a full teaching load that includes graduate courses and teaching sedimentology to

engineering students. Stephen Ruppel, a senior research scientist at the bureau, taught Advanced Reservoir Geology with Fisher for the last decade and described him as an engaging, highly knowledgeable and entertaining instructor. Ruppel said he always had a little advice for students when it came to Fisher’s lessons: “Listen to what he says; he’s the one who developed these ideas so he knows what he’s talking about.”

Fisher is also always willing to pick up courses, a trait Kerans found a little maddening at times, particularly when he thought younger faculty members might be dodging the classes.

“I said more than once, you don’t need to volunteer for this stuff. You’ve done more than your fair share,” Kerans said. “But, of course, he’d wind up doing it, and he’d do a great job.”

During his decades of teaching, Fisher supervised or co-supervised more than 150 graduate students. Many were international and went back to their home countries to take on leadership positions in the industry or government. These include places such as Colombia, Venezuela, Mexico, Turkey, China and of course, Brazil, where Fisher played a foundational role in building the country’s oil and gas industry.

For three years Cloos co-taught with Fisher a course on natural resources and the environment. He described Fisher’s teaching style as distinctive and invigorating, one that would weave current events, historical anecdotes and political and policy knowledge into practical lessons.

“He was one of these guys who always had a story to go with whatever the subject is,” Cloos said. “He was always able to put in parts of the story that aren’t found in a book.”

Fisher took on his first student in 1966, serving as a master’s adviser while working as a researcher at the bureau. That student, Bill Galloway, went on to have a tremendous career in industry, at the bureau, and in the department, winning the Society of Sedimentary Geology’s Twenhofel Medal nine years after Fisher won the award. Galloway has since had a long professional and personal relationship with Fisher. He remembers Fisher from those early years as an educator who would always take time for his students and loved to talk about science.

Galloway was so taken with Fisher’s love for the science that he laughingly recounts predicting at the time that Fisher would never become director of the bureau or take a similar position that took him away from his research. Among Galloway’s many memories was Fisher’s initial reaction after reviewing his first draft of his master’s thesis.

“He said, ‘The first thing you want to do is take the first third and throw it away,’” Galloway said. The first third of the thesis was a “grand review of the geology of the Gulf of Mexico Basin,” which Fisher was quick to point out could be found in plenty of books. It was during that time that Fisher gave Galloway a piece of advice that he still hears echoing in his head when writing papers.

“If you’ve got something to say, you need to say it in the title, the abstract and the illustrations,” Galloway remembers Fisher telling him.

That was Fisher.

“He always plowed straight ahead, and he got stuff done,” Galloway said.

Forty years later, it was that same attribute that would lead to Fisher becoming the Jackson School’s founding dean, taking the helm of the school he helped create. Faulkner was looking for someone to launch the new school and put it on a solid course for the future. The job was difficult, to say the least. It involved tying together three academic and research units with distinctly different identities, cultures and budgets. And it needed to be done in a way that

followed the guiding principles of the Jackson gift, which stated the money was not to be used “for daily bread” — meaning the funds weren’t for covering regular operational costs or programs, but to tie the university’s geosciences assets together and build them into something truly exceptional. Given the energy, abilities and strong will needed to handle such a unique job, Faulkner said he didn’t seriously consider anyone but Fisher.

“We were looking for leadership that would push it to advance,” Faulkner said. “Bill had the credentials and the eminence and the drive to do it.”

Now that he’s retired, Fisher hopes to keep his office at the Jackson School. He said he’s going to take it easy, which none of his colleagues really believes, and will finish a paper he’s been working on and having fun with during the past year.

“I think I’ve got one more in me,” he said. “And maybe it will turn a few heads.”

The University of Texas at Austin

Web Privacy | Web Accessibility Policy | Adobe Reader