QUANTUM SHIFT

Realtime seismic imaging may seem like

science fiction, but Mrinal Sen has other ideas.

BY CONSTANTINO PANAGOPULOS

I

magine this: It’s 2035 and the U.S.’s new national science ship is on a mission to investigate signs that a massive earthquake is about to hit the Pacific Northwest. Below deck, gigabytes of data from a dozen sensors pour into the vessel’s quantum computer.

On the science deck, a 3D image of Earth’s subsurface instantly reveals the fault and its surrounding geology. The scientists instruct the crew to bring the ship closer to a region of high tectonic strain. They quickly conclude it’s a false alarm: A seafloor bulge detected by early warning satellites was just a passing slow tremor, nature’s safety valve alleviating the tug of war between tectonic plates.

The science vessel turns to its next mission. In Galveston, Texas, a drilling ship is being fitted to tap geologic hydrogen. The quantum science vessel will sail ahead and find the undiscovered reservoirs.

Back in the present, this scenario seems like a distant dream. But at least one part of it could be closer to reality than many think.

Quantum computing has made important recent advances. Although the technology still has hurdles to overcome, its supporters say that the quantum computing revolution, especially in big data crunching (think materials science, cancer research, climate modeling and, of course, seismic imaging), is just around the corner.

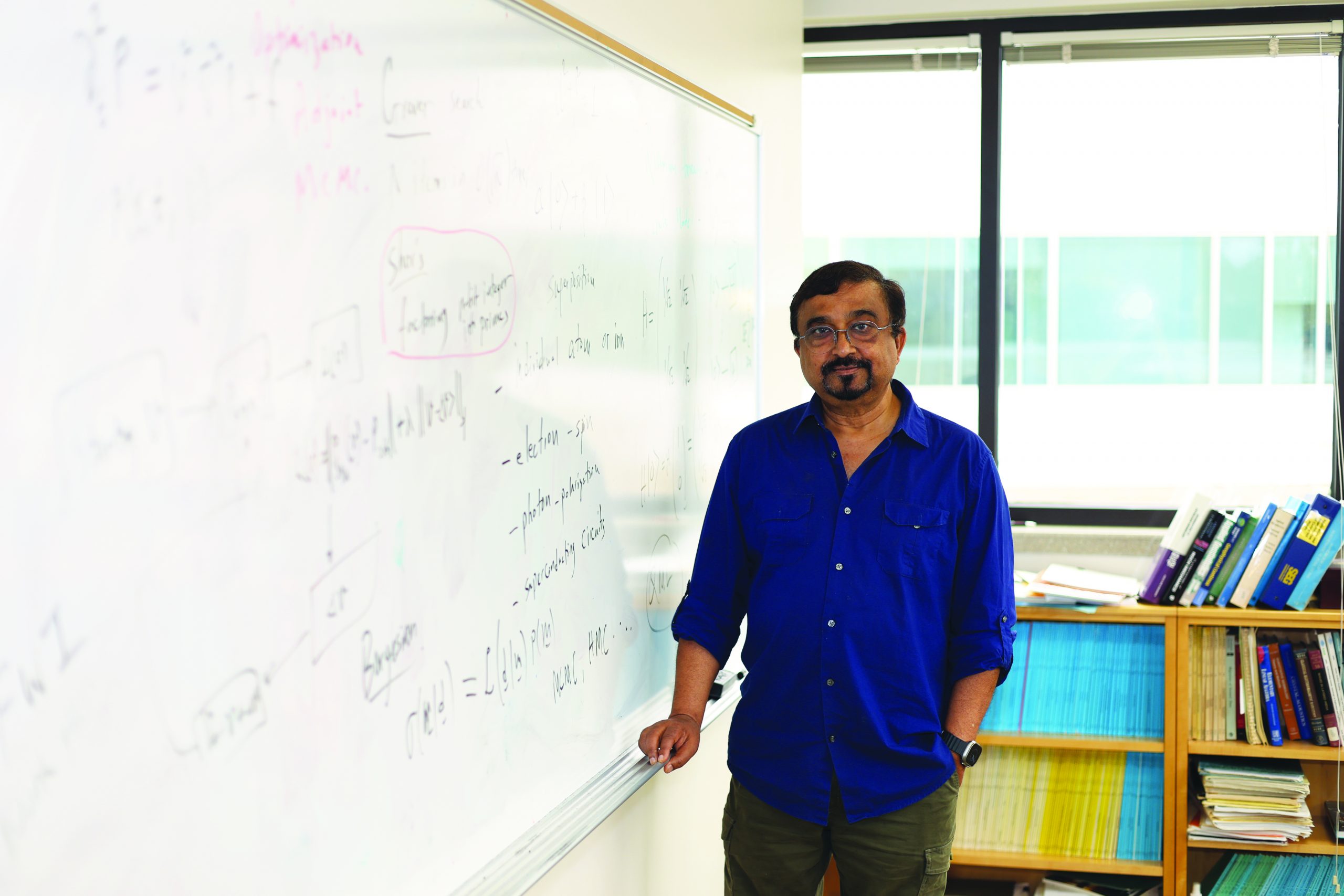

Mrinal Sen, a geophysics professor at The University of Texas at Austin, has tasked himself with getting the geosciences ready for the bright, quantum future. At the top of his agenda is to adapt seismic imaging algorithms to work with existing quantum computers — algorithms that will be the foundation of real-time seismic imaging, long the holy grail of seismic research. He also wants to establish a new center of quantum computing research for the geosciences and attract industry support to fund the effort.

The nascent technology is not without its detractors. In early 2025, after Sen announced that he’d be leading a workshop on quantum computing in geophysics, his inbox filled with emails claiming that the technology isn’t mature enough and that his workshop is too soon.

Sen disagrees. Having correctly predicted the transformative impact on the geosciences of first neural networks, then parallel computing, machine learning and artificial intelligence, Sen has good reason to be confident that the time to introduce quantum computing to the geosciences is now.

“(Quantum) programming is a different way of thinking to classical computing,” Sen said. “It’s time that we start to investigate the applicability of our algorithms to quantum computing so that we can understand what the issues are in doing that.”

There’s still some way before the technology is ready for geoscientists to run their large-scale algorithms, but Sen wants people working on and talking about the problem now so that the science is ready to make the most of the quantum future.

A SEISMIC PROBLEM

The goal of seismic imaging is to turn vibrations in the Earth into an image of what lies underground. The image can then be studied to illuminate earthquake faults, oil reserves, mineral deposits, underground carbon storage locations, groundwater, or simply geology. It’s the bread and butter of many researchers at the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics (UTIG), where Sen works.

But it’s not an easy task. Earth’s subsurface is noisy and unpredictable. Constructing a useful seismic image typically requires many seismic waves recorded from many sources and at many strengths and wavelengths. That’s terabytes of information, all of which need to be pruned, cleaned of noise and balanced for uncertainty.

Next, scientists analyze the seismic waves’ strength, speed and frequency and match them against a model of the Earth, adjusting the model bit by bit to deduce what the waves passed through on the way.

It’s a lot of painstaking mathematics to find the best probable solution from many alternatives. A seismic image of the subsurface is not an image in the traditional sense; it’s just the likeliest picture of the subsurface after all other possibilities have been eliminated.

Even with supercomputers such as Lonestar6 at the Texas Advanced Computing Center, which UTIG’s researchers frequently make use of, a single seismic image can take weeks of analysis and hundreds of supercomputer hours to generate.

But what if you had a computer that could do the calculations instantly?

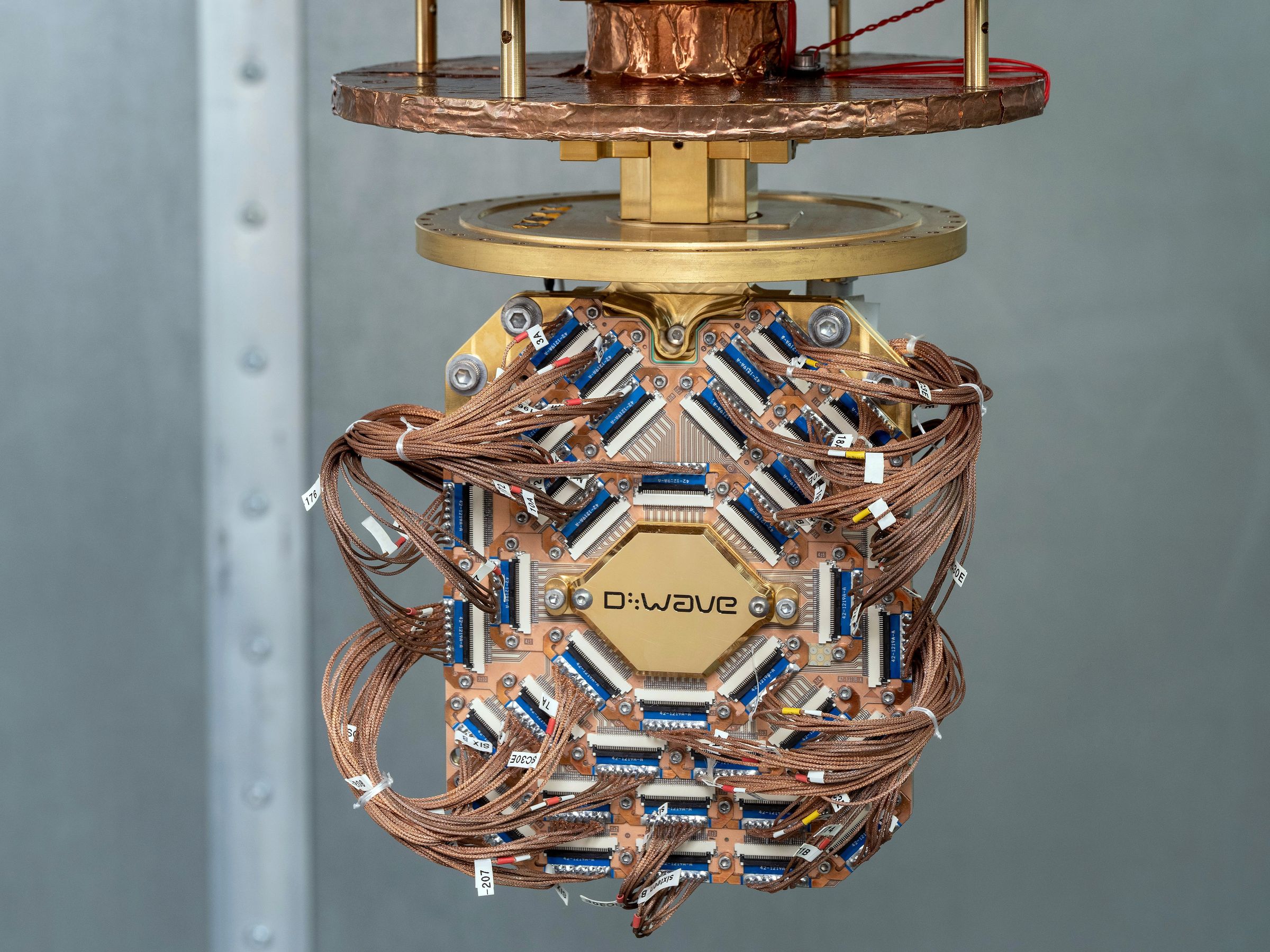

In 2024, Sen and colleagues at Stanford University ran a basic seismic imaging problem on a Canadian quantum computer called D-Wave.

The machine solved the problem and generated an outline of the likeliest subsurface characteristics in the image. The problem and data involved were both very small, but the solution generated was a milestone in computational geophysics. More importantly, it worked. The test was proof that the algorithms used for seismic imaging can be mapped onto the bizarre world of quantum mechanics.

“Programming for quantum computers is completely different because nothing is certain. Everything is probabilistic,” Sen said. “I find that kind of fun.”

The quantum mechanics behind quantum computers give them key advantages over traditional computers when it comes to solving certain problems. A quantum computer’s units of information, called qubits, are not just 1s or 0s — they are simultaneously 1, 0, and (when looked at probabilistically) everything in between. Qubits are also entangled, which means that a quantum processor carrying out operations on its qubits can act on them all at once.

These two properties are what make quantum computing so exciting for big data crunching — because they allow quantum computers to perform multiple probabilistic calculations simultaneously.

“It has the advantage of doing massive parallel computations,” Sen said.

That advantage, which scales exponentially the more qubits are working together, means quantum computers will theoretically be much faster at processing the vast amounts of data generated by seismic imaging.

“For real-time imaging, we have to be able to read a huge volume of data — which is a bottleneck right now,” Sen said.

But some quantum computers such as D-Wave have another trick that lets them quickly tackle probabilistic problems. These machines use a technique that lets the qubits pick out the best answer by finding the problem’s lowest energy state.

It’s called quantum annealing, and it works like this: Imagine you are trying to find the lowest point on a very long graph with many dips and peaks, but you can see only a very small portion at a time. In conventional methods, an algorithm takes a starting point, computes part of the graph, then decides whether to keep going. Quantum annealing is like a cheat code: It tunnels through the graph until it can’t reach a lower point — the problem’s lowest energy state — saving a lot of unnecessary computations.

It’s a technique that’s especially promising for seismic imaging, where data is particularly noisy and needs to be cleaned up to show an optimized image.

A QUANTUM SOLUTION

How well quantum computers will work in real-world settings is difficult to pinpoint. The D-Wave tests (and similar tests on quantum emulators) were successful, but the experiment was not designed to show how much quicker the quantum processor was at solving the problem. According to Sen, though, it needn’t be.

“Not every algorithm will work on quantum machines, but for those that do, it will be like night and day,” he said. “This will really be a quantum leap.”

The signs from those developing the technology are encouraging. In a recent announcement, Google claimed its latest quantum chip, Willow, had performed calculations in a few minutes that would take the fastest supercomputers longer than the age of the universe to complete. Critics pointed out that the benchmark tests, while impressive, did not resolve the technology’s wider problems, including the reliability of its results, which still fell far short of traditional computers.

Putting quantum machines to use isn’t as easy as swapping out a chip. Quantum processors are incredibly delicate, and keeping their qubits in a quantum state gets trickier the more you put on a chip. They’re also very susceptible to electromagnetic noise, which causes them to give unpredictable answers. These obstacles have kept commercial quantum computing a decade over the horizon for more than 30 years.

“Programming for quantum computers is completely different because nothing is certain. Everything is probabilistic. I find that kind of fun.”.

— Mrinal Sen

Sen, however, is optimistic that the technology is finally learning to overcome the worst of those obstacles.

“When people say quantum computers are not there yet, it’s the correct statement for today,” he said. “But when I started my career 35 years ago, parallel computing in seismology was a dream. People thought that we’d never do large-scale computations like that. Look where we are now.”

Today, parallel computing is the gold standard for processing seismic data, thanks in large part to sophisticated software developed by researchers, including Sen, that take full advantage of the technology’s benefits. Doing the same with quantum computing and seismic imaging would be a revolution in the geosciences.

With the initial tests in his pocket, Sen together with researchers from Stanford and other leading U.S. universities are rallying support from geoscientists, physicists and computer scientists to establish a national institute for quantum computing in the geosciences.

The proposal is still awaiting a decision from the National Science Foundation, but even without NSF funding, Sen already has plans to advance quantum computing research for the geosciences. At UTIG, he’s advising a graduate student, Sohini Dasgupta, on developing a quantum computing algorithm for monitoring underground storage of carbon dioxide. He’s hired students and postdoctoral researchers to develop more advanced quantum algorithms for future seismic imaging tests. He’s also tapping the institute’s internal funding to kick-start more ambitious real-time seismic experiments. And at the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, where he teaches, Sen plans to introduce quantum computing concepts into his machine learning classes.

In the meantime, Sen and his collaborators are doing what they can to mobilize the scientific community and garner industry funds to keep momentum going.

Sen’s vision is an industry-funded quantum computing research program at UT Austin. Whether that materializes depends much on how his research is received at conferences and workshops throughout the year. But Sen has every reason to be optimistic.

“We’ve had some good conversations with companies, and there’s a lot of interest. There’s an understanding that we’ve been doing this for years, that we know how to tackle these problems,” Sen said. “It’s not big money for them, but it will be good support for more students, and the long-term rewards of what we’re doing really could be huge.”

The University of Texas at Austin

Web Privacy | Web Accessibility Policy | Adobe Reader