LIFE ON THE ROCKS

Professor Charlie Kerans Retires After 40 years at UT Austin

By Monica Kortsha

Your Text Here

It’s 8:30 a.m. on a bright Sunday morning, and cars are whizzing by on the highway near Austin’s Pennybacker Bridge. On the side of the road, a class of about 25 undergraduate geology students is studying the limestone cliffs that line the passage.

The spot may be busy now, but during the Early Cretaceous? There wasn’t much going on here at all, save for the gradual piling up of carbonate material at the bottom of a shallow sea.That steady geologic story is exactly why Professor Charlie Kerans has brought his field methods class here. The sediment built up into solid limestone that persisted even as the sea went away. When the Capital of Texas Highway cut through it, it revealed a slice of geologic history.“It’s a good place to learn,” Kerans said, standing with a hammer in hand to nail up magnified photos of rock samples from the outcrop so students can more clearly see the grains. “The rock is all gray. But the story is all in the details.”

Kerans is one of the foremost carbonate geologists in the world. He has made a career of reading rock and teaching people the skills they need to make their own geological interpretations. From UT students, to industry groups, to geological societies, Kerans estimates he has led hundreds of people to outcrops across Texas and around the world.

By learning to read the details in the rock, students in Kerans’ field class are learning skills that can be applied to reservoir characterization the world over, particularly in oil and gas. Kerans hints at the importance of this skill. “Geology isn’t just a puzzle,” he said, the class gathered around a white suburban that Kerans has been sketching stratigraphy on with a dry erase marker. “It’s a multibillion-dollar puzzle.”

The humble local roadcut doesn’t have oil field connections. But it has much to offer as a teaching exercise. That makes the outcrop a fitting spot for Kerans’ final field trip as an instructor at The University of Texas at Austin. From the very beginning, Kerans has dedicated his career to research and education.

Big Impact

Kerans retired from the Jackson School of Geosciences in August after 40 years at UT.

He spent the first 20 years as a researcher at the Bureau of Economic Geology, where he led its Reservoir Characterization Research Laboratory (RCRL) — one of the bureau’s longest-running and most successful research consortia, bringing in $30.6 million over the years so far. He spent the next 20 years as the Robert K. Goldhammer Chair in Carbonate Geology at the Jackson School’s Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, where he focused on teaching students. He also served as department chair from 2016 to 2020.

During his career, Kerans mentored generations of geoscientists. He directly advised 23 doctoral students and 31 master’s students, not to mention the hundreds of undergraduate students he taught in the classroom and the field. Many of his former students now work in the oil and gas industry. Ted Playton is one of them. He earned master’s and doctoral degrees working with Kerans during the 2000s. He is now a senior geoscience adviser at Matador Resources and was a geologist at Chevron for 17 years before that.

Playton said that the experiences he had as a graduate student gave him an edge working in a range of reservoir environments around the world, particularly Kazakhstan. “This background that I developed working with Charlie very much influenced my career and opened up doors that were really important for me and my family,” Playton said. “He’s very insightful and knowledgeable about the kinds of problems the industry has.”

Carbonate rocks are made of calcium carbonate — CaCO₃. Most of this material comes from myriad marine life forms, including the reef builders such as corals and their ancient counterparts, as well as plankton, snails and clams, either directly from the animal remains or from CaCO₃ that’s dissolved into ocean water and precipitates out when the chemistry is right.

Many of the world’s best-known carbonate deposits are the remains of paleo reefs — huge conglomerations of fossils and sediment. Their origins create porous and fractured rocks that make for excellent oil reservoirs. Scientists estimate that up to 60% of the global hydrocarbon supply is contained in carbonate rocks. The world’s largest oil fields — including many of those in the Permian Basin — are hosted in carbonate strata.

However, while the pores and fractures can help oil and gas accumulate, they can also create complex pathways for flow that can complicate oil and gas production and cause hydrocarbons to be left behind. But a clear understanding of stratigraphy — of geological layers and how they interface and interact — can help producers navigate the reservoir environment and improve recovery.

According to Pat Welch, a past president of the West Texas Geological Society (WTGS), the work of Kerans and his students in the Guadalupe Mountains brought much-needed clarity to the stratigraphy of the Permian Basin. Their geological studies helped untangle a region that had been known by contested formation names and other pieces of incomplete and idiosyncratic data.

“He’s got this fantastic stratigraphic framework that ties all of the old formation names from all these different areas,” Welch said. “From the outcrops in different mountain ranges into the subsurface, everything had different names and it was very confusing. It takes an incredible amount of effort, time and intelligence to put it all together, and Charlie and his students graciously shared their knowledge with WTGS members through countless field trips, presentations and poster sessions.”

In 2022, Welch presented Kerans with an Honorary Life Membership award to the society to honor his contributions to the geology of West Texas and his role in sharing the knowledge. Kerans’ research has also earned him top awards from professional societies. This includes the Society for Sedimentary Geology’s Francis J. Pettijohn Medal for excellence in sedimentology (2015) and the American Association of Petroleum Geologists Robert R. Berg Outstanding Research Award (2022).

Call of the Wild

Although well versed in industry applications now, Kerans was a relative late bloomer when it came to understanding how his scientific research could be applied outside of academia. When he was a graduate student, his interest in carbonate geology was driven by innate curiosity and a desire to explore the world — especially its most remote parts.

For his doctoral research at Carleton University in Ottawa, Canada, Kerans spent his summers near the Arctic Circle studying 1.2 billion-year-old reef complexes, some of the oldest on Earth. Working his field site situated between Great Bear Lake and the Arctic Ocean involved being dropped off by float plane in the Canadian bush at the start of the summer and being picked up at the end of it.

Kerans’ summer job as an undergraduate geology student at St. Lawrence University informed his decision to study in the wilderness. On paper, the job had little to do with geology. He worked at remote Atlantic salmon fishing camps in Nunavut, Canada, that were operated by the father of a close friend. The environment was inspiring. “I just really enjoyed being out in the bush there,” Kerans said.

The salmon camp experience also helped him during his first year of graduate school. When he ran out of money in the field, he headed to a nearby fishing camp. He and his field partner worked for the funds to fly home.

After earning his doctoral degree, Kerans went to Australia to work as a postdoctoral researcher at the Geological Survey of Western Australia with Phillip Playford, an influential geologist whose stratigraphic research laid the groundwork for the western Australian oil industry.

Playford was an excellent teacher. Kerans learned all about the geology of Canning Basin, a preserved paleo reef akin to the Permian Basin, and Shark Bay stromatolites, analogs to Earth’s oldest fossils created by sheets of cyanobacteria and carbonate grains. He also accompanied Playford as he documented Aboriginal songs on a tape recorder and was invited to visit sacred sites. “That wasn’t really our business; we were doing geology,” Kerans said. “But Playford’s approach was when you’re doing geology and you’re doing fieldwork, you’re out in the world and you’re interacting with everything in it.”

Although Kerans’ position was funded by the Western Australian Mining and Petroleum Research Institute, Kerans’ understanding of how his research could actually be put to use came later. There was a barrier between the academic data and the industrial application.

That all changed when he came to Texas in 1985.

As a research associate at the bureau, Kerans became immersed in a research institute where the data he collected was meant to inform discernable outcomes. The research had to bring tangible benefit to its funders, which were largely the University Lands, the State of Texas and the industry members of the bureau’s newly formed research consortia groups.

Each consortium organized research around a shared subject. Companies paid a membership fee to have first access to consortium data and interpretations, and provide data of their own to the researchers.

In 1987, after short stints working on a Department of Energy-funded nuclear waste storage assessment and with the University Lands Advanced Reservoir Initiative, Kerans and colleague Jerry Lucia formed the Reservoir Characterization Research Laboratory (RCRL), which focused on studying geology related to carbonate-hosted oil reservoirs, initially within the Permian Basin, and later across the state and internationally.

Kerans credits his bureau colleagues, especially Lucia and Senior Research Scientist Don Bebout, with showing him the ropes. “They’re the ones who educated me. This is how you take your knowledge and make it useful,” he said.

Learning how industry applied the geological data and interpretation to oil and gas production brought a new perspective to Kerans’ work. It didn’t stifle his innate curiosity or his love of wild places. But it did help channel it toward research that could lead to new knowledge and useful applications for industry.

Kerans turned his attention to the Guadalupe Mountains of West Texas and New Mexico and the surrounding areas that contained world-class outcrops serving as analogs for subsurface reservoirs of the Permian Basin. His research would help to modernize the understanding of the geologic structures and how they were connected to the oil fields of the Permian Basin.

It also led to a nickname that’s an honor all its own: “The Guad Father.”

Exploring the ‘Guads’ Anew

From computer modeling to seismic imaging to lidar, the 1980s and ’90s offered a whole new way to see the world. In the Guadalupe Mountains, Kerans saw a place ripe with opportunity, both for academic understanding and stakeholder return. There was just one problem.

When Kerans started at the bureau, he was told that fieldwork wasn’t a priority because the bureau was more focused on applied subsurface geology rather than academic fieldwork. Kerans, who was aware of the bureau’s rich history of fieldwork, recalls just nodding along. “I just thought, ‘Yeah, well, I’m just going to ignore what that guy said about fieldwork. I will probably be able to figure out something.’”

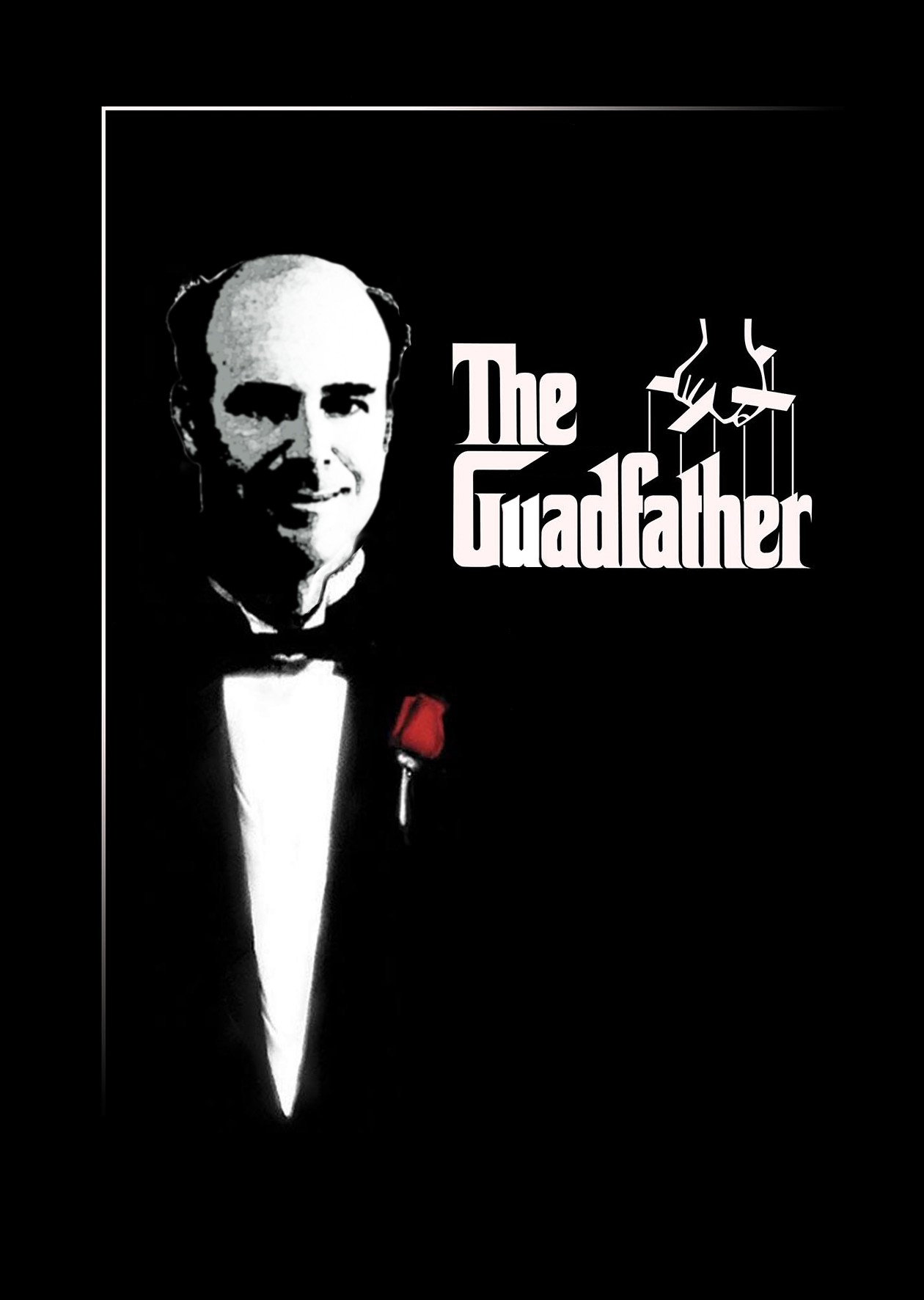

At the RCRL, Kerans did exactly that. His fieldwork focused on documenting large-scale geological features, from canyon walls to eventually the entire Permian Basin-facing sides of the Guadalupe Mountains and nearby Delaware Mountains. He used aerial photography from small fixed-wing aircraft as well as the Texas state pooling system’s police helicopter to gather critical images. During the 2000s, Kerans collected ground-based and aerial lidar data with the help of Jerry Bellian and others at the bureau. These were some of the earliest geological applications of the technology and resulted in remarkable three-dimensional details of the mountain ranges.

The ambitious scale of the work made for some key advances in a relatively short time frame. In 1987, the team started mapping porosity and permeability in outcrops of the San Andres Formation, one of the most productive geological units in the Permian Basin. Within 18 months, Kerans, Lucia, and fluid flow modelers Graham Fogg and Ekrem Kasap at RCRL had put together a geostatistical map and simplified fluid flow simulation that helped illuminate how injecting water to recover oil — known as “secondary recovery” — could be applied to subsurface reservoirs in the units.

Mapping the mountain faces between 2010 and 2012 was Kerans’ first foray into large-scale lidar mapping. Although it took 18 months to process the data, it proved to be an important milestone — bringing the bureau into the world of digital mapping.

The survey also helped lead to the discovery that one of the most well-known geologic features in the area — Carlsbad Caverns — is actually controlled by a fault system that developed during the Permian period. The sprawling caverns are located inside the foothills of the Guadalupe Mountains in the northeast portion of the range. The lidar point cloud, combined with detailed surface mapping by the bureau’s Chris Zahm and Maren Mathisen, revealed a trench-like structure that aligned with the boundaries of the cave. Bounding the cave system on both the northwest and southeast sides were two parallel faults, which Kerans and Zahm referred to as the “Cave Graben.” These faults were the primary influence on fluid flow that led to the growth of the main cave passageways. That meant that faults that formed in the Permian some 250 million years ago set the stage for a cave that would form millions of years later.

The RCRL members were the first to know about findings, but through research papers, book chapters and presentations, Kerans shared the research with professional geology groups across the state and the region.

According to Stonnie Pollock, a member of the West Texas Geological Society, sharing the data has helped geologists working in the oil and gas industry come to agreements about geological formations that were previously hotly contested — such as the Clear Fork Formation. There are still naming issues when it comes to institutional paperwork and leases, Pollock said, but he is grateful that members of his profession are on the same page. “At least us geologists can all agree,” Pollock said. “I don’t have much ground to up and say we need to call it this instead of this, but when Charlie or one of his students do, people tend to pay attention better.”

‘What Stories Can You Tell?’

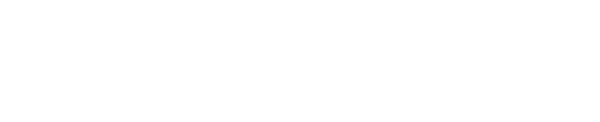

Students and consortia members often accompanied Kerans on his field trips to the Guadalupe Mountains and later to other West Texas locales, such as Pecos River Canyon. During the late 1980s, one of the consortia members was a young geologist at Marathon Oil named Scott Tinker — who would go on to lead the Bureau of Economic Geology as director from 2000 to 2024.

Tinker recalls learning about carbonates at every scale from Kerans, from micropores all the way to whole canyon walls. “He puts all of this together and then will tie that to well-log data and seismic and other measurements,” Tinker said. “So, you start integrating all those together and you get a better picture.”

The RCRL member trips usually included a hike up the Permian Reef Geology trail, one of the world’s best exposures of a paleo reef. Over a 2,000-foot vertical climb, the trail offers a complete cross-sectional view from bottom to top — like “you pulled the plug out of the bathtub and the water ran out,” said Kerans, who co-edited a guidebook on the trail published by the bureau.

But according to people who joined Kerans in the field, the most memorable part about hiking the trail may have been watching Kerans on the way down. Tinker, Playton and Pollock all mentioned Kerans’ tradition of running right down the mountain side, racing any contenders who were up to the challenge. (Kerans reports his best time at 28 minutes. He suspects his downhill runs and having a double knee replacement later in life might be related.)

Playton, Kerans’ former graduate student, said that simply seeing Kerans in action on the outcrop was inspiring to him as a young geologist. But he said an early field experience with Kerans also taught him the value of having a sense of humor when something goes wrong.

According to Playton, when issues arise, Kerans’ first instinct usually is to laugh — with the specific timbre depending on the severity of the blunder. Playton recalled becoming well acquainted with what he calls the “Kerans Cackle” his very first time in the field with him.

They were camping in West Texas when a bad storm rolled in. Playton spent the night fighting a losing battle with a leaky tent. In the morning, Playton realized that Kerans had spent the night in their suburban. When Playton, utterly exhausted and soaked in the early morning, opened the door to the SUV, Kerans couldn’t stop laughing at the pitiful figure standing before him. “He just starts laughing uncontrollably for like five minutes,” Playton recalled. “And this was probably the second night that I’ve known him.”

After warming up with some coffee, Kerans told Playton that their field plans had changed. They were going into town to get a hot breakfast. To Playton, that simple gesture proved to him that his adviser had his back. “You know, he’s hardcore and intense, but he really cares about the welfare of his students,” Playton said. “There’s always something weird that happens in the field, right? But then, afterward you laugh about it.”

Just getting out in the field helps set the stage for great stories, said Kerans. To him, it’s one of best parts of being a field geologist. “I always kid my petroleum engineering friends, ‘What stories can you tell? I had a rough time at the golf course or something?’” Kerans said. “For a geologist, we have adventures built into things.”

Still, the field can be a dangerous place. Tinker and Kerans happened to share what they agree is their most harrowing experience together: a rattlesnake bite and a missing person in the middle of the night during a weeklong industry field trip down the Pecos River in West Texas. The group was in canoes and didn’t have a cellphone signal or a vehicle. So, Kerans and Tinker set off in the middle of the night, jogging about 7 miles toward a ranch house so they could call 911. While riding with EMS back to the camp to pick up the snakebite victim, they found the missing person wandering along the road and picked him up. And as an emergency helicopter was taking the snakebite victim to a San Antonio hospital where he made a full recovery, they got another shock. The day was Sept. 11, 2001. Through the windows of the ranch house where EMS had brought the victim, Kerans and Tinker saw the Twin Towers falling for the first time on a TV screen.

Tinker said seeing how Kerans kept his cool as problems just kept piling up is something he will always remember. “It’s a long story, but I think it’s an important one because it describes the respect he had. He had everyone working together,” Tinker said. “It was pure chaos, and still, he was able to complete the job and get everybody on board.”

Passing the Torch

Starting in 2008, Kerans started to expand the scope of his field research. In addition to the desert mountains of West Texas and New Mexico, he started studying the Pleistocene limestones of San Salvador Island in The Bahamas and the nearby Turks and Caicos Islands.

To the casual observer, the environments might seem like polar opposites. To geologists, the connection is clear: They’re both paleo reefs — one ancient and the other more modern. The Permian reef of the Guadalupe Mountains is over 250 million years old. The Bahamian island limestones are Pleistocene, dating to about 125,000 years ago. What’s more, the fossil reefs share a shoreline with modern iterations, complete with corals, sharks and tropical fish.

Kerans was interested in using the more refined geologic record in The Bahamas to learn more about carbonate geology from a different, more modern perspective. He was also interested in a new research question: What do the paleo-shoreline deposits of The Bahamas record about past sea-level rise, not just across the region as a whole, but in particular places across the island? And what can that tell us about how contemporary sea-level rise might play out along shorelines around the world? “It’s remarkable how you see the change even in the last few thousand years,” Kerans said. “There are differences in how the beaches are accumulating or eroding on a regional basis, so it’s got a big impact.”

A new era of technology — such as lidar and video-equipped drones, differential GPS and advances in computer map making — made it possible to collect and catalog the landscape in detail. Kerans also started leading field trips under the waves, with the group suiting up in scuba gear to investigate underwater outcrops.

And when Benjamin Keisling, a glaciologist who studies the Greenland ice sheet, was hired as a research assistant professor at the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics in 2022, Kerans saw an opportunity to get at these questions from a totally new perspective, while also getting students involved. That’s how the course “Ice Sheets, Sediments and Sea Level” was born. It was launched during Spring 2024 and was held again during Spring 2025.

The class combines Keisling’s and Kerans’ areas of expertise — physics-based ice sheet modeling and field-based carbonate geology, respectively — and culminates in a trip to San Salvador Island in The Bahamas. Here, students apply skills and approaches from both Kerans and Keisling to collect data on sea-level rise for a group research project. “It’s a hard class — but it’s a very integrative class that shows what geosciences and geology is traditionally, and also what it can be,” Keisling said. “It showcases the multiple strengths of the discipline — the different skills and perspectives that you can bring as a geoscientist to do the work we do.”

According to undergraduate Liesel Papenhausen, a fourth-year environmental science major concentrating in geology, the class brought a whole new perspective to how different areas of the Earth influence one another. “I really loved how interdisciplinary the class was because it brought together two types of science that seem almost antithetical,” said Papenhausen, who took the class in 2024. “I mean the Earth system is so connected that you can go to The Bahamas and learn things about the Laurentide ice sheet. That’s so unintuitive and so amazing.”

The class rolls together what Kerans is known for — amazing field experiences, carbonate geology and critical questions. Keisling noted that it’s not just working with Kerans and his decades of knowledge that helped make the class an unforgettable and innovative success. Kyle Fouke and Scarlette Hsia, two of Kerans’ graduate students, were there too. Keisling said that he saw in them the same sensibility and skillfulness in the field that make Kerans great. “It’s wonderful the way that he’s passing on that knowledge and training geologists that are going to continue to have that same eye for detail and a sense for figuring out Earth’s story, while also branching out and using their own methods, their own perspective, and taking their own approaches,” Keisling said.

Playton said that type of educational experience is something to cherish long after graduation. He sums up the impact of working with Kerans at the start of his own dissertation. After a dedication to his wife, and mother and father, he writes: “To Charlie Kerans, who taught me to walk on rock.”

|

|

Impact of a 40-Year Program of Carbonate Field ResearchIn his final DeFord Lecture, Charlie Kerans shares highlights from his career studying carbonate geology. WATCH: bit.ly/4hwVqpt |

The University of Texas at Austin

Web Privacy | Web Accessibility Policy | Adobe Reader