Shining a Light on How Water Filters into Inner Space Cavern

December 1, 2022

By Charles Kerans, professor in the Department of Geological Sciences

Inner Space Cavern is a spectacular limestone cave system near Georgetown, Texas, just off of I-35, that has been a focus of numerous Department of Geological Sciences researchers including the vertebrate paleontologists Ernie Lundielius, Chris Bell, and students. It has also provided a laboratory for paleo climate research by Jay Banner and students over the past 20 years. In recent years the department has showcased the cave system during its new undergraduate (NEO GEO) and new graduate student field trips.

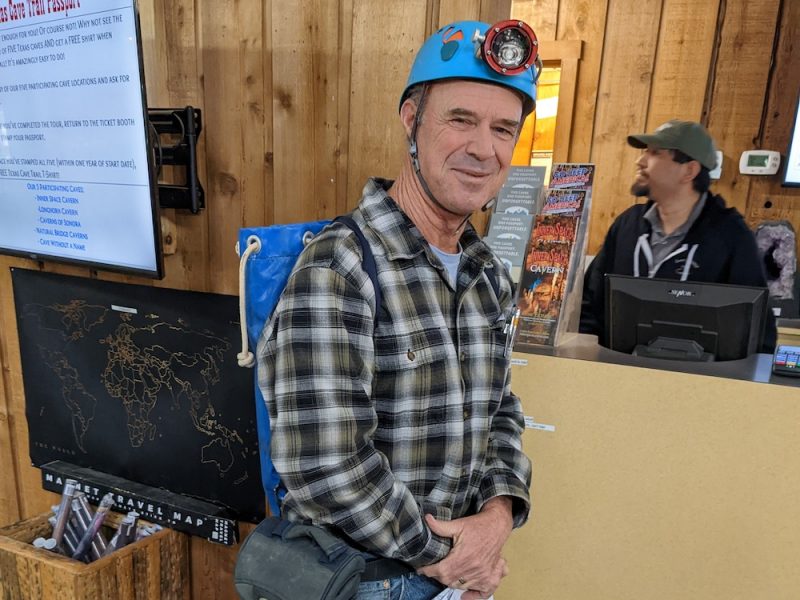

This August, during a planning trip for the NEO GEO trip made by Chris Bell and Charlie Kerans, and then during the NEO GEO trip led by Nicola Tisato, the group noticed a distinctive host rock succession that might provide insight into what controlled the localization of the roof of the cavern system. As a follow-up to confirm these observations, Tisato and Kerans took a quick drive up I-35 to Inner Space Cavern to shine a light (literally and research-wise) on the specific host-rock layers they suspected controlled the original cave morphology. This succession of limestone strata observed in the walls of the cave include a shallow tropical shelf layer, a fossil reef unit made of rudists (Cretaceous clams), high-energy carbonate sands/gravels, a microbial mat layer (tidal flats?), and a distinctive layer of silicified evaporite (most likely gypsum). The gypsum layer likely represented a hypersaline pond back in the Cretaceous (Albian), approximately 100 million years ago. While the fossil gypsum layer (now replaced by silica) is only 40-50 cm thick, the highly soluble nature of gypsum in the presence of groundwater suggested that it served as a potential “highway” for downward percolating rain water. The fossil evaporite layer is also overlain by a relatively thick and mechanically strong limestone bed that now serves as the main roof support.

In addition, during the visit, they downloaded data from two instruments placed inside the cave. These data loggers include a high-precision thermometer used primarily for teaching purposes and a drip-rate sensor that measures the number of droplets falling from a stalagmite. Detailed descriptions of the key layers controlling the shape of the cavern await future trips. The University of Texas researchers have been fortunate to be able to have access to this amazing cave system for research and teaching purposes through the generous permission of the Inner Space Cavern Management.