October 24, 2023

Read Izzy's exciting tale of mapping in the wilderness with the Alaska Division of Geological and Geophysical Surveys (DGGS).

Anyone who knows me would describe me as extreme. I live a life full of adventure, and, for me, it doesn’t get much more adventurous than the Alaskan interior. Upon the completion of my master’s degree from the University of Alaska Fairbanks, it was only fitting that I became an intern with the Alaska Division of Geological and Geophysical Surveys (DGGS), an organization that works to better our understanding of Alaska’s geology and geological resources. The DGGS Minerals Group is currently pioneering a regional-scale mapping campaign to form a more complete understanding of interior Alaskan critical mineral resources. My advisor, Dr. Richard Ketcham, and I have since formed a collaboration with the DGGS to work on constraining tectonic controls of Eocene cooling in the Yukon-Tanana Upland in the interior for my PhD project, primarily utilizing Dr. Ketcham’s technique of expertise: apatite-fission track dating. Although most of our analyses are performed in the lab, we go to great lengths to collect our samples: between the thick brush, giant mosquitos, and aggressive bears, you must be a special kind of geological maniac to fight for your life over a piece of granite. Read on for my chronicle of a day in the life of a DGGS scientist, which has proven to be the most extreme fieldwork I’ve ever done.

A blaring alarm starts my field day at 6:30 am. I first throw on my field clothes, which consist of a long-sleeved shirt, pants, belt, and boots. Those are my base layers, but I carry two extra warm layers, extra socks, a hat and gloves, and rain gear in my pack to be prepared for all weather conditions. After getting dressed, I head to breakfast at 7:00 am for a hearty meal and lots of coffee. I am not a big fan of eating early in the morning, but between the long hours and lengthy traverses, this job demands extreme caloric intake. After breakfast, I make sure I have all my sample collection gear in my pack and on my person. This includes my rock hammer, extra sample bags, my tablet, three forms of emergency communication (a radio, an inReach satellite communication device, and a satellite phone), an emergency survival kit and first aid kit (in case we ever get stranded overnight), and bear protection. My gear weighs about 20 pounds before a rock is even collected! The most important piece of gear I carry is definitely my sunglasses. They protect my eyes from both the midnight sun and from flying rock chips after hitting samples. Don’t ever forget your eye protection!

After receiving my geologic mission for the day, I hop in the helicopter at 8:00 am to fly to my assigned traverse where we conduct our mapping and collect samples. No traverse is “typical” here in Alaska. Though we plan our traverses based on older geologic maps from this area, many of these maps are decades old and do not reflect the actual terrain we will encounter in the field (hence why DGGS has launched this regional mapping campaign). Since we have helicopter support, we try to plan our traverses to have more elevation loss than gain to avoid unnecessary treks uphill. Our helicopter work ends up being more efficient in terms of samples obtained within a given period of time, and we’re able to cover vast tracts of the study region on flights ranging from 10-20 minutes to upwards of 45 minutes. We first fly to the end of the traverse, mark a few potential landing zones from the air, and then head up to our starting point to find a good place for the helicopter to drop us off. Sometimes there is a nice place for the helicopter to land; however, because of how forested the interior is, we often have to exit the helicopter for a “toe-in” landing. This is when only the fronts of the skids of the helicopter touch the ground along a slope and the pilot hovers over the ground while we crawl along the skids to get out. Though it can be a little scary, I would rather have a toe-in landing than an uphill walk that takes all day!

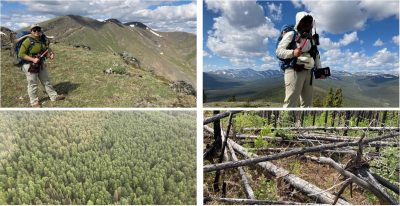

Traverses are usually between 2-5 miles long and range from high above the tree line to swimming through brush to crawling over fallen trees in a previously burned forest. We might even see all of that in one day! Sometimes we walk across five geologic contacts in one day, while other days we encounter the same rock type for the entire traverse. We are often swarmed by mosquitoes, but very rarely do we see a bear or moose (hopefully off in the distance). Sometimes we are soaked by rain or pelted by hail for part or all of the day. I might go from wearing all my layers to none of them by the end of the day, or even zip my face up in a mosquito shirt.

After a long day of traversing, we make our way to a landing zone. When we are high on the ridge line, it can be easy for the helicopter to land as long as the wind is not too strong. Most of the time, though, we either go an extra 1-2 miles down to the swamp or cut ourselves a landing zone for pick up. There is an important cost-benefit analysis to landing zone selection: if you walk down to the swamp, you usually don’t have to cut any trees, but it can be tough to go down a steep slope with a pack full of rocks—especially when there are bushes to fight through or trees to crawl over. By this time, my pack probably weighs between 30-35 pounds. It is also a bummer to get your boots wet at the end of the day, particularly if your extra pair is already soaked back at camp. It can be better to cut yourself a landing zone on top of the ridge because a different crew can land there later and finish mapping the rest of the ridge. Despite this, cutting down trees with a hand saw can be rather exhausting and time consuming, meaning you have less time to collect samples. Through a few bad choices, I have learned that some trees are too big and not worth the time to cut down if you can help it!

After we get picked up, we return to camp between ~4:00-4:30 pm, but our work is far from done for the day! We drop our samples off at the rock saw to be sliced, photographed, and dried. We collect a sample every ~1000-1500 feet, so we often have a lot of samples, anywhere from seven to 15. I then quickly change into my Crocs and grab a cold drink. Once the samples have been photographed and cataloged, we take them over to the office tent for geochemical analysis. We have a Bruker handheld x-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometer in the field for immediate verification of the different lithologies. Many of the rock types look similar or are extremely fine-grained, so geochemical analysis is an important tool for our mapping projects. Additionally, it saves us from spending lots of time running XRF analysis on them during the fall when DGGS is processing thousands of data points across the map area.

After XRF processing of my samples, it is time for dinner (~7:00 pm). After dinner, I take a second look at my samples and update my notes based on the geochemistry. Then, I drop my rocks off to be boxed up and taken back to Fairbanks for long term storage. If I’m not too tired, I sometimes use my free time in the evening to do something extra fun. In 2022, I enjoyed panning for gold in the evenings when we were camping in Chicken, AK. This year, we stayed at Chena Hot Springs for part of the summer, so I would take the time to soak in the hot springs. All great things to do after a long day in the field!

I spent 6 weeks in the field this summer. It is hard work, but very rewarding. I am extremely grateful for the opportunity to be part of such a cool project and contribute to our understanding of the Alaskan interior with my PhD research. Dr. Ketcham came up this summer to get the true Alaskan geologist experience, and we shipped home 18 boxes of samples! Stay tuned to hear about the results of my project, and maybe some more crazy field stories that I’ll collect along the way.