July 5, 2023

This June for Pride Month, the Science, Y'all! Twitter highlighted a selection of influential LGBTQ+ geoscientists. In case you missed it, we've compiled the threads into a blog post to archive it forever on the internet, making it easier to refer back to. Please get in contact if you'd like to contribute a profile to this topic!

To start off, check out this Q&A by Elenita Makani Nicholas from the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability that explores the importance of discussing gender and sexuality in the geosciences!

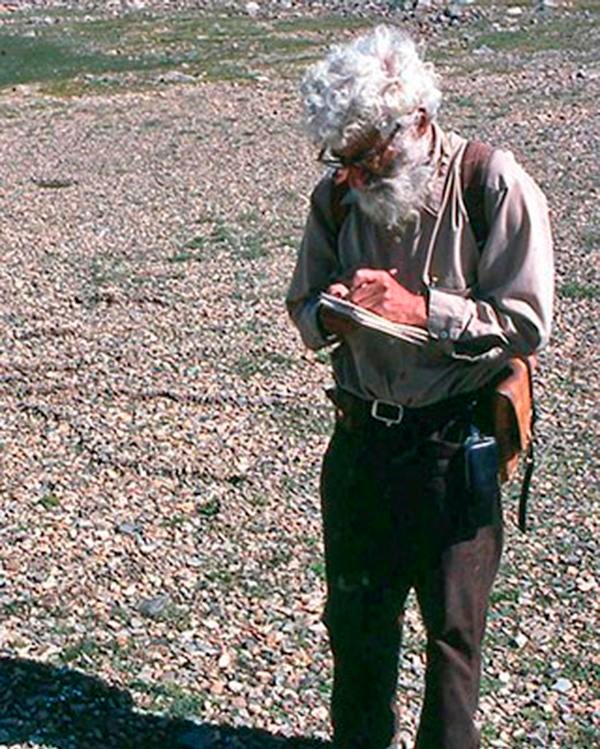

Dr. Clyde Wahrhaftig was a glacial geologist and LGBTQ+ leader in the geosciences. In 1919, Dr. Wahrhaftig was born in Fresno, CA. His mom took classes at the UC Berkeley, so Dr. Wahrhaftig became familiar with Berkeley & its geology.

In 1941, Dr. Wahrhaftig graduated with his bachelor’s degree in geology from the California Institute of Technology. He began working for the USGS and continued while he got his Ph.D. from Harvard in 1953. At the USGS, Dr. Wahrhaftig studied Alaskan geology, particularly surrounding coal deposits, ranging from the Brooks Range to the Kuskoquim Mountains to the Alaska Range. Alongside fellow geologist and his partner, Dr. Allan Cox, Dr. Wahrhaftig published the novel paper, “Rock Glaciers in the Alaskan Range.”

In 1960, Dr. Wahrhaftig became a faculty member at the University of California, Berkeley. After joining UC Berkeley, he continued to do field work, especially in the Sierra Nevada. He was awarded the Geological Survey of America’s Kirk Bryan Award after publishing his paper, “Stepped Topography of the Southern Sierra Nevada.”

Dr. Wahrhaftig mapped and interpreted Yosemite’s past ice ages for nearly 50 years and even left money in his will for the research to continue—which finished only recently in 2019. Dr. Wahrhaftig was also an environmentalist: working with the National Park Service to create the Bolinas Lagoon bird sanctuary and using his geologic perspective to advocate for sustainable forestry practices as a member of the California Board of Forestry.

He was elected the chairman of the Geological Survey of America’s Environment and Public Policy Committee in 1971. He also aimed to make geosciences more diverse and accessible, serving as the chair of the GSA’s Minority Participation in the Earth Sciences in 1971. This committee held the First National Conference on Minority Participation in Earth Science and Mineral Engineering the following year. Dr. Wahrhaftig worked with educational programs in Hunter’s Point to take students who are underrepresented in geosciences on field trips throughout the Sierra Nevadas and the Bay Area more generally. Notably, Dr. Wahrhaftig came out as gay in his acceptance speech for GSA’s Distinguished Career Award. He said,

“Receiving this award for longevity has made me realize that my time to do good is running out. So I have decided to use the opportunity you have given me…I am now going to provide a role model for a minority that has been demanding a modicum of the civil rights the rest of the country possess – a minority that has managed to survive largely because it is invisible. It is a minority to which Allan Cox and I belong. We are both homosexuals. The group whose attitudes I wish to affect are those of you who are not homosexual, but who may find yourselves with students, subordinates or colleagues who are. I ask you to recognize that homosexuals can make as much of a contribution to science and humanity as anyone else.

In the last 20 years the homosexual (or gay) community has moved out of the shadows, and there are gay student organizations on almost every campus. So it is likely that some gay students who enter geoscience will not be closeted as Allan and I were. You will have to deal with them as they are. The other group whose attitudes I wish to affect are gay students who would like to become geoscientists, but are afraid to because they think being gay and being a geologist are incompatible.

I want my life, and Allan’s and my relationship, to tell them that this is not so. If they are lucky, as we were, their love and their careers will sustain each other. And I hope that by making this revelation here, I contribute in some small way to the creation of a society with a sufficiently intelligent, open and compassionate attitude toward sexuality.”

At 74 years old, Dr. Wahrhaftig passed away from heart failure in 1994. His legacy lives on as a geologist, educator, and advocate.

Read more about Dr. Clyde Wahrhaftig here or read his GSA memorial here.

Barbara P. Nash, a geologist and geophysicist who even has a mineral named after herself!

Dr. Nash received both her bachelor’s degree and doctorate from the University of California, Berkeley in geology in 1965 and 1971 respectively. In 1970, she was appointed the Director of the University of Utah’s Electron Microprobe Laboratory—capable of analyzing specimens that are 1/10-1/100 the size of a fingernail thickness. In 1978, Dr. Nash became a professor in the Department of Geology and Geophysics at the University of Utah.

She has published a number of important papers in the fields of igneous petrology, mineralogy, and geochemistry. In particular, Dr. Nash studies the geochemistry of volcanic rocks with an emphasis on volcanic rocks produced by Yellowstone hotspot eruptions over the past 16 Myr.

In 2003, Dr. Nash used her expertise as a renowned scientist and experiences as a transgender woman to write a compelling letter to the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine advocating against the publication of the anti-transgender book The Man Who Would Be Queen. In addition to her geologic teaching, Dr. Nash designed a course on transgender studies.

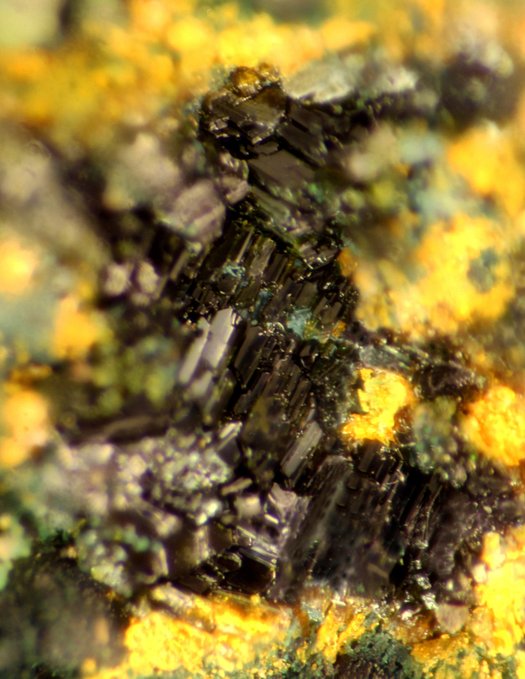

Part of Dr. Nash’s expertise also included mineral identification. She helped identify several minerals with Joe Marty, who is a Salt Lake City mineral collector, including nashite—which Marty chose to name after Dr. Barbara Nash because of all her help!

Of Dr. Nash, Marty said, “Since she has been so involved in describing these new minerals, the authors felt it was important for her to be recognized.”

Marty first discovered nashite in 2010 within the abandoned St. Jude uranium mine in Colorado, but didn’t collect it for analysis until 2011. Nashite, or sodium calcium vanadate, is blue-green and part of a mineral class called decavanadates that designates minerals containing V. They form when oxygen reacts with vanadium ores close to the surface in abandoned, moist mines. The color is unusual for this type of mineral and is the first of its kind to have an unusual atomic structure that results in its blue-green color!

In response to nashite being named after her, Dr. Nash said,

“I’m thrilled and honored to have received this recognition from my colleagues, but I can understand that for most people it probably isn’t obvious just how satisfying it can be to have ‘ite’ added to your last name.”

Dr. Barbara Nash retired recently and was named Emerita Professor in 2019. Throughout her career, Dr. Nash has aided in the identification of 75 minerals accepted by the International Mineralogical Association!

Learn more about Dr. Nash and the discovery of nashite here and read here about her letter to National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine advocating against an anti-transgender book.

UTIG’s very own Dr. Benjamin Keisling is a glaciologist, as well as an advocate for justice in geoscience and geoscience education development. He has been fundamental in the expansion of AGQ, the AGU’s LGBTQ+ organization.

In 2013, Benjamin Keisling obtained his bachelor’s degree in physics from Saint Olaf College in Minnesota. He went on to obtain his master’s and doctoral degrees in geosciences from the University of Massachusetts (UMass) Amherst in 2015 and 2020 respectively. Dr. Keisling was then appointed a postdoctoral fellow at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory at Columbia University until 2022. In 2022, Dr. Benjamin Keisling joined UTIG as a research associate!

Dr. Benjamin Keisling uses climatic modeling to understand the dynamics of ice sheet evolution, with a focus on Greenland and Antarctica. By investigating the processes that shaped these surfaces in the past, particularly with respect to changes in climate, Dr. Keisling hopes to better anticipate how those mechanisms will change ice sheets in the future and improve predictions for climate responses such as sea-level rise.

He uses both numerical modeling of ice sheets and climate as well as geological information to examine these processes. For example, Dr. Keisling investigated the seasonal temperatures of the Greenland ice sheet during the last deglaciation in the early Holocene. In this study (published in the Geophysical Research Letters journal), Dr. Keisling and his colleagues merged ice core reconstructions, which are often restricted to annual averages, with climate simulations to model changes in ice volume with regard to seasonal climate variations to determine the Holocene ice volume minimum.

Dr. Keisling’s research has already investigated new mechanisms involved in ice sheet evolution. In a study published in Geology, Dr. Keisling and his colleagues modeled the Greenland ice sheet’s early stages to research the extensive canyon network underneath the ice. With numerical models that accounted for previous topography, climate, and ice sheet growth, the researchers were able to identify a new process for landscape erosion in Greenland that aids in the analysis of geologic features below the Greenland ice sheet.

In addition to his novel research, Dr. Keisling has also been heavily involved in cultivating a more inclusive geosciences field. He’s been a mentor for STEMSEAS, a chair on the Lamont Diversity, Equity, & Inclusion Task Force, a founder of Columbia Climate Organizations, a Co-organizer of the “Cultivating Leadership for Change and Justice in the Geosciences” Workshops, a convener of the Second National Conference on Justice in Geoscience, and much more.

Importantly, Dr. Keisling has also been the AGQ/gAyGU Coordinator and Organizer, run by both AGU and Out to Innovate (previously known as the National Organization of Gay and Lesbian Scientists and Technical Professionals) since 2018. In an interview about building safe spaces for the LGBTQ+ community in the geosciences, Dr. Keisling reflected on his experiences with AGQ/gAyGU and noted that in the past, events had been relatively small and mostly attended by white gay men. With encouragement from previous organizers, Dr. Keisling worked to diversify and expand the network of geoscientists in AGQ. In this interview, he said:

“I created surveys, did a lot of tweeting, advocated through my position on AGU’s Diversity and Inclusion Advisory Board, and organized with past, present, and future leaders of the community to make LGBTQ+ programming at the Fall Meeting more visible and inclusive. Over the last couple of years a lot of what I have done is an attempt to ensure that future generations of geoscientists coming to that meeting find a robust representation not only of their scientific interests but also ways to connect with other geoscientists that share some of their identities and experiences.”

As for future work, Dr. Keisling has drawn attention to the particular need to create inclusive and affirming spaces for geoscientists who are trans, nonbinary, and/or people of color:

“Historically these are groups that have not been centered in our community building, and that needs to change. There is tremendous opportunity to build solidarity among affinity groups that serve different populations, and in order to do that work effectively we have to ensure that our community is meeting the needs of geoscientists who experience marginalization along multiple axes of their identity (e.g. race, gender, and disability status).”

When asked about barriers in starting initiatives to cultivate inclusive spaces, Dr. Keisling said,

“The LGBTQ+ geoscience community is incredible and if I listed everyone who has helped to overcome these challenges it would use up the rest of the space allocated for this Q&A. I think there is no challenge that we can’t overcome if we continue to be as interconnected, brave, and resilient as we are now.”

Although early in his career, Dr. Keisling has already accrued a number of accolades for both his research and justice advocacy. He has won both the NSF Graduate Research and NSF GROW Fellowships, as well as an International Ocean Drilling Project Post Expedition Award and a Presidential Citation from AGU. Dr. Keisling was also presented with the UMass Campus Climate Improvement Grant and UMass College of Natural Sciences Excellence in Diversity & Inclusion Award.

You can learn more about Dr. Keisling on his website here, and read “A conversation on building safe spaces for the LGBTQ+ community in the geosciences”, in which Dr. Keisling is interviewed and quotes are from, here.

https://500queerscientists.com/

https://earth.stanford.edu/news/qa-why-discuss-sexuality-and-gender-geosciences

https://smv.org/learn/blog/pride-paleontology-highlighting-more-lgbtq-scientists/