June 18, 2020

Effective communication is an integral part of both the scientific and research processes, allowing others to validate and build off of past studies and work. Academics, researchers, and scientists are often taught the value of communication in science, though the skills needed to accomplish this in any meaningful way may not always accompany the transmission of this message. Much has been written on the need for effective science communication and education, including a study published in PNAS, where Fischhoff, a researcher at Carnegie Mellon, notes that while “people can choose not to do science, they cannot choose to ignore it. The products of science permeate [our] lives” (2012). Fischhoff further details that effective science communication informs people about the benefits, risks, and other costs of their decisions. He concludes that the goal of science communication is not necessarily agreement but fewer, more informed disagreements.

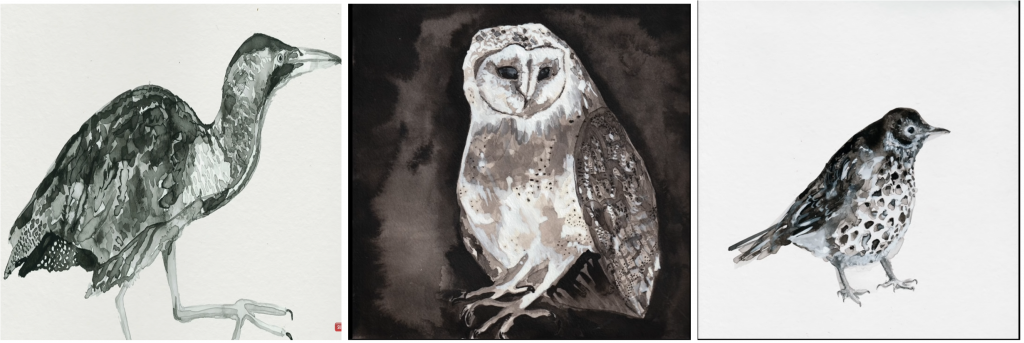

Kappel and Holmen (2019) provide researchers and scientists with a varied list of aims to keep in mind when communicating science, including collecting and making use of local knowledge as well as utilizing distributed resources to be found . On that front, educators have found that creative means of expression, such as music and visual art, to be effective teaching tools which occupy the space at the interface of science, arts, and community (Clark and Button, 2011). Publicover and colleagues (2017) and Song (2012) explore the value of interdisciplinary education that incorporates both art and science to promote intellectual development through creativity and foster a sense of community.

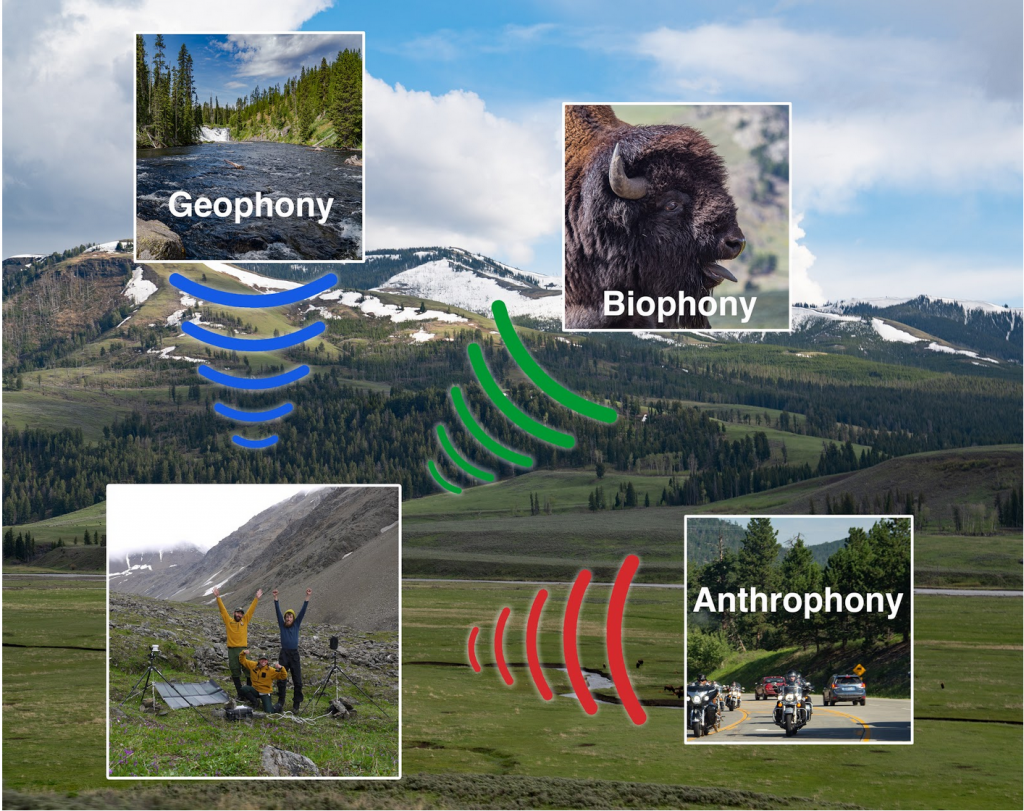

Researchers have also begun to use sounds and even music as ways to communicate science, developing terms, including soundscape geophony, biophony, and anthrophony, to describe the new ways sound is being employed in a research capacity. Pijanowki and others (2011) detail the science of soundscapes in various landscape environments; and, in his 2012 work, Bernie Krause describes the origin of music in nature. In recent times, researchers (Wodak, 2017) employed popular music as a means to convey the effects of anthropogenic climate change that begins to blur the lines between art and science.

We (Jackson School PhD students – Natasha Sekhon, ’21, and Stacie Skawrcan, ’23) recently interviewed an artist at the intersection of science and music. Cosmo Sheldrake is a London-based multi-instrumentalist composer, musician, and producer who has captured sounds and earth processes in his songs. Cosmo has worked with Bernie Krause, a well-known soundscape ecologist, to write a song about deep time, ‘Pliocene’ and as a result of ‘Tardigrade Song’ has been offered the opportunity to collaborate with researchers in the Department of Evolutionary Biology at the University of Edinburgh. We got the chance to sit down with him and talk about the importance of science communication, methods of dispersing science to a wider audience, and the value in recording sounds as part of conservation.

On how his childhood experiences influenced his current practice (0:00):

“I guess in a weird way everything did as it does. My mum teaches Mongolian overtone chanting and an interest in music from many different parts of the world. So I grew up with her large record collection of quite obscure music from different corners of the globe. My dad is a biologist but also plays music as well. I grew up outdoors a lot [with] bird spotting and thinking about biology and biological concepts. And my brother is also a biologist and researches fungi and mycelium networks. I’ve been around that my whole life. And I studied anthropology and lots to do with ecology and natural sciences [at the University of Sussex]. The history and philosophy of science, ecology, and phenomenology. All of that wormed its way into the music, for sure…”

On the history of soundscape and the value of it for Cosmo (1:24):

“A lot of the field recordings of [Bernie Krause] have demonstrated quite unbelievably convincingly that actually one of the best ways of telling the health of an ecosystem or its biodiversity is through sounds itself. And if you convert a field recording of [such] as space into a spectrogram and analyze the frequency it makes against time… [Bernie] has recorded before and after events of selective logging and on comparing the spectrograms. You can count the species that are not there anymore… [compared] to a visual inspection which is limiting, especially in tropical ecosystems. There is also fascinating work being done by [Prof.] Steve Simpson and Timothy Gordon (his PhD student) at the University of Exeter. They’ve found that if you play the sound of a healthy coral reef to a dying coral reef, it encourages the fish to come back and the coral reef can come back to balance. They call it acoustic enrichment… which is very exciting…”

On the importance of using sounds to explore climate change (4:22):

“Art has the ability to communicate more powerfully. There is only so much you can tolerate when it comes to [climate change] facts and this sort of doom and gloom [as the general public]. After a while, it doesn’t help, it doesn’t mean anything. It’s endless statistics. It has no influence on action or on how someone is going to go and carry on with their day. Fundamentally you can saturate people [with facts] but people are only responsive to that for maybe 5 – 10% of the time. There needs to be engagement in a different way. So for me, it’s just, on the one hand, making music out of these objects from where I’m sitting is enough because it buries the stories into the sound themselves. But obviously, there is another aspect when you can communicate where those sounds come from. When I perform or play shows, I give parts of histories of where each sound comes from. So you have that in your head, you’re thinking about it. But it [then] also converts it into an emotional experience, which you can relate to in a different way. For me it’s essential to use music and sounds as a way of exploring these topics. Even if it is just the sound of a healthy and then the sound of a dying reef, next to each other. The fact that you’re listening to it, rather than somebody saying coral reefs are dying. The fact that you can hear it. Encountering that on an emotional level is a different thing entirely…”

On making science more accessible to a larger audience (6:29):

“The room for art and science collaboration is huge. One thing that science is not amazing at is communication. And often with [academic] journal entries that most of science communication is through, in Nature and other world-renowned top of the line scientific journals, [the audience] is miniscule [compared to the general public] in terms of the impact they have. If it is particularly resonant with people, it will get turned into headlines and people will take one snippet of it. But that’s about the best you can hope for with scientific papers or communication in that way. Yet, if you frame it in the right way, some of these are truly groundbreaking, and can change the way you think about things. And a good way to expand on engagement is to engage more with artists.”

On the impact Cosmo wants to make (8:19):

“Good question, I don’t really know. I tend to sort of think [about] living most of my life in [the] immediate future. I take one thing at a time for the most part. But one thing I’m working on, the way the world sounds and the way things vocalize is, one of the major impediments to communicating that is the fact that we listen to everything on headphones or stereo speakers. Given that everything we listen to is deeply polyphonic, I mean the world itself is deeply polyphonic and sounds are coming from everywhere at once. And to understand an ecosystem is to understand those relationships. So one thing I’m trying to explore and get my head around more is polyphony in general. Thinking about more than one voice, more than one story at once. And also just trying to make music for multi-channel setups which can better explore the reality of how we actually hear and experience the world. And then the natural problem with that is how people experience that on a DIY base, not everyone has a multi-channel studio. One thing I’ve been doing is to come up with an app which is essentially a way to release music in multiple channels. So I can put a piece of music out and say to you guys, that at 7PM tonight is going to be streaming and it’s got 16 [musical] parts. So you need 16 friends to get together, you plug your phone into a portable speaker and it’s going to stream at that time in the app. The idea being a way or platform or medium by which people can listen to things from many sound sources but in a DIY way. It brings back a kind of intimacy to listening to music and it’s a group experience, especially with the kind of Spotify. First it was iPods that fragmented the album and now it’s even more, you can get anything at any time and in any way. You know it’s become such a private and isolated experience, everyone is disconnected on headphones. It’s a way of bringing back intimacy or community or sharing into [music]…”

On sounds Cosmo wants to record (13:29):

“Well, I’ve been thinking recently about how to record plant[s] and fungi. There has been some interesting work done by this woman called Monica Gagliano and [she] has a book called Thus Spoke the plant. A lot of people have been doing stuff with data sonification where they record low voltage current in plants and then turn them into sounds. But it’s also true that plants make acoustic sounds themselves, as do trees, and potentially fungi as well. I’m more interested in the acoustic emanations of the things themselves. But using ultrasonic microphones and various other techniques you can also record plants acoustically as well. So I’ve been thinking about that and trying to build ultrasonic microphones and record that. And also there is this recording from the 70s that I’ve been working with, which is recording action-potentials in fungi. Essentially using the same technique, they use to measure brain nerve impulses [but] on fungi. They feed this fungal network [through] a block of wood. And you slowly hear these pops speed up as it gets more and more excited about its imminent feast. I’ve also been interested in radio astronomy and the sounds from space, that still includes a lot of data sonification. I’ve got a friend who is a radio astronomer who records the storms on Jupiter’s moons. And then uses the electrical impulses to make little sculptures and makes them move by the currents from Jupiter’s moons. There is a lot of fun that can be had but these are the two things I’m most thinking about, at the moment.”

Etymologically speaking, ‘science’ derives its roots from the Latin word scientia, which translates to knowledge or understanding. The Oxford English Dictionary defines science as “the intellectual and practical activity encompassing the systematic study of the structure and behaviour of the physical and natural world through observation and experiment.” Science is for everyone, and its communication need not be limited to science outreach. By collaborating with those in different disciplines, especially ones involving art and music, science can be made much more engaging, allowing it to reach a wider audience and have a larger impact.

References:

Clark, Barbara, and Charles Button. “Sustainability transdisciplinary education model: Interface of arts, science, and community (STEM).” International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education (2011).

Fischhoff, Baruch. “The sciences of science communication.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110.Supplement 3 (2013): 14033-14039.

Kappel, Klemens, and Sebastian Jon Holmen. “Why science communication, and does it work? A taxonomy of science communication aims and a survey of the empirical evidence.” Frontiers in Communication 4 (2019): 55.

Krause, B. (2012). The great animal orchestra: finding the origins of music in the world’s wild places. Little, Brown.

Pijanowski, Bryan C., et al. “Soundscape ecology: the science of sound in the landscape.” BioScience 61.3 (2011): 203-216.

Publicover, Jennifer L., et al. “Music as a tool for environmental education and advocacy: artistic perspectives from musicians of the Playlist for the Planet.” Environmental Education Research 24.7 (2018): 925-936.

Wodak, Josh. “Shifting baselines: Conveying climate change in popular music.” Environmental Communication 12.1 (2018): 58-70.