May 8, 2023

This March for Women's History Month, the Science, Y'all! Twitter highlighted a selection of influential women geoscientists. In case you missed it, we've compiled the threads into a blog post to archive it forever on the internet, making it easier to refer back to. Please get in contact if you'd like to contribute a profile to this topic!

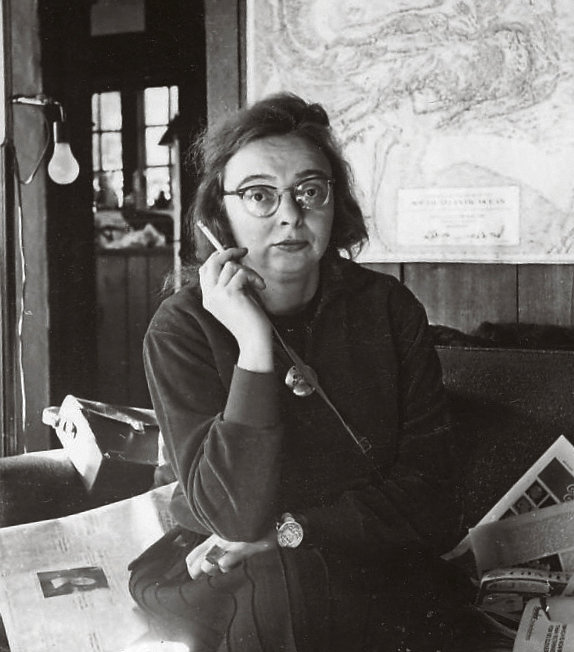

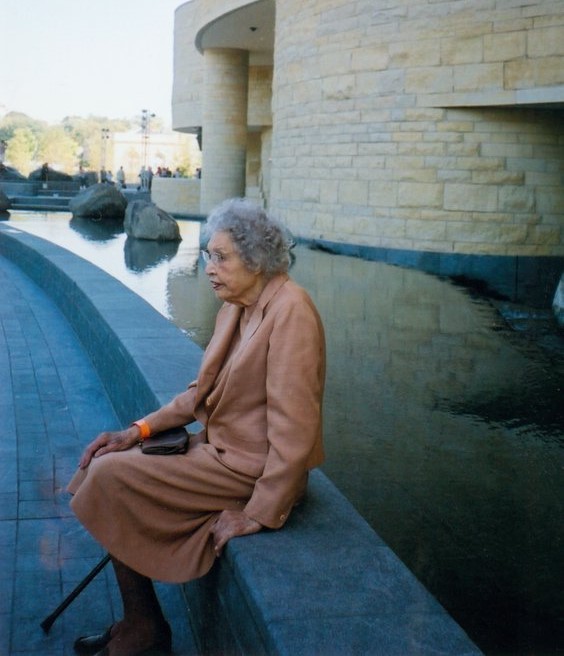

Marie Tharp: Creator of the first global ocean floor map.

Born in Ypsilanti, MI, Tharp’s father was a soil surveyor for the US Dept of Agriculture. As a child she would accompany her father in the field & through this, was introduced to map-making. Despite moving constantly for her father’s job & attending 17 different public schools, she took a class called Current Science in school in AL and went on class field trips to study trees and rocks. After working on her family’s farm for a few years following her high school graduation, Marie Tharp enrolled at Ohio University.

She graduated in 1943 with bachelor’s degrees in English and music (and four additional minors)! During WWII, more women were recruited into petroleum engineering. She had taken a geology class in undergrad,so Tharp attended the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor and got a master’s degree in petroleum geology in 1944. Several years later, Tharp was one of the first women hired at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory.

She collaborated with Dr. Bruce Heezen to identify downed military aircrafts with photographic data. Dr. Heezen collected bathymetric data when on Vema, a research vessel. As a woman at this time, Tharp was not allowed to work on ships, so she drew maps using Vema data, in addition to data from Atlantis, (WHOI’s research ship), and seismographic data from underwater earthquakes.

Tharp and Heezen published the first map of the Atlantic in 1957, with Tharp’s maps illustrating the mountains, ridges, and canyons covering the seafloor. It wasn’t until 1968 that Marie Tharp was allowed to go onto a research vessel.

In 1977, Tharp and Heezen published a complete world map of the ocean floors. The maps created by Tharp revealed the presence of mid-ocean ridges, covering more than 40,000 miles around the world. Tharp’s contributions to mapping the global seafloor provided ample evidence to support the plate tectonics theory.

Read more about Marie Tharp and her discovery of mid-ocean ridges here.

Dr. Sudipta Sengupta—a structural geologist, who aided in establishing India’s permanent research station in Antarctica!

Dr. Sengupta was born in Calcutta, India, but as her father was a meteorologist, the family spent a lot of time in Nepal. Spending time so close to the Himalayas, Dr. Sengupta developed a passion for mountains. She was even trained as a mountaineer at the Himalayan Mountaineering Institute by Tenzing Norgay, the first man to climb Mt. Everest!

Dr. Sengupta obtained her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in applied geology, and afterwards, a doctorate in structural geology (1972), all from Jadavpur University in West Bengal. Whilst completing her PhD and for a bit after, she worked for Geological Survey of India. Dr. Sengupta then researched at Imperial College in London and Uppsala University in Sweden. At the latter, she studied the Norwegian Caledonides. In 1979, Dr. Sengupta once again worked at the Geological Survey of India, this time as a senior geologist.

Three years later, she became a lecturer at Jadavpur University. In 1981, India sent its first expedition to Antarctica. Two years later, Dr. Sengupta and marine biologist, Dr. Aditi Pant, were the first Indian scientists who were women to go to Antarctica.

For two months, the scientists on this mission conducted research and set up the first Indian station, Dakshin Gangotri, in Antarctica. In addition to helping to establish this base, Dr. Sengupta also conducted exciting research on the Schirmacher Hills in East Antarctica.

India and Antarctica were both part of Gondawanaland, a supercontinent preceding Pangea. Because of this, mountain ranges in Southern India and Eastern Antarctica are similar! Dr. Sengupta’s research helped to establish this connection and built the foundation for future studies.

In 1991, Dr. Sengupta won the prestigious Shanti Swaroop Bhatnagar Award in Geological Sciences, and also received the National Mineral Award and Antarctica Award from the Government of India. She also published the successful book Antarctika, published in 2012.

Read more about Dr. Sengupta and her experiences in Antarctica here.

Hydrogeologist Zelma Maine Jackson.

Maine Jackson grew up in the Gullah-Geechee Nation in South Carolina with her grandmother. It was her grandmother, a midwife, who first piqued Maine Jackson’s interest in geology because she learned that red clay was used to treat iron deficiency in women.

Maine Jackson grew up in the Gullah-Geechee Nation in South Carolina with her grandmother. It was her grandmother, a midwife, who first piqued Maine Jackson’s interest in geology because she learned that red clay was used to treat iron deficiency in women.

At 7 years old, Maine Jackson moved to a U.S. army base in Heilbronn, Germany. She quickly grew fluent in German, which she maintains today, and took advanced science and math courses in her German school— beginning calculus when she was 10 years old.and with Dan Silver for WA state Governor William Booth Gardner, who was a proponent of environmentalism. With the encouragement of Silver, Maine-Jackson went back into geology to oversee the Hanford cleanup through the Nuclear Waste Program, where she worked for almost 25 years.

In addition to being a founding member of the National Association of Black Geoscientists, Zelma Maine Jackson is a trustee at The Nature Conservancy in South Carolina to protect sea turtles and other wildlife in the ACE Basin.

She also was on the State of Washington African American Affairs Commission throughout the careers of four governors, the Washington State Community Economic Revitalization Board for two terms, and the Washington State Dept. of Natural Resources as an advisory member.

Read more about Zelma Maine Jackson and her experiences in geoscience here and here.

Mary Golda Ross – aerospace engineer.

Ross was born in Park Hill, OK, which is close to the capital of the Cherokee Nation, Tahlequah. Her childhood was steeped in Cherokee culture and history, and her parents were both Cherokee citizens. Ross’s great-great grandfather, John Ross, was the former Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation.

Ross was born in Park Hill, OK, which is close to the capital of the Cherokee Nation, Tahlequah. Her childhood was steeped in Cherokee culture and history, and her parents were both Cherokee citizens. Ross’s great-great grandfather, John Ross, was the former Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation.

After high school, Ross studied mathematics at Northeastern State Teacher’s College in Tahlequah and graduated in 1928. Following graduation, she taught math and science at public schools for almost a decade. In 1937, she became an advisor at the Santa Fe Indian School—a government-run boarding school for Indigenous children in New Mexico. During the summers as a teacher, Ross took classes at the Colorado State Teachers College (now known as the University of Northern Colorado) to earn a master’s degree in mathematics in 1938.

Due to WWII, Ross started working at Lockheed Aircraft Corporation in Burbank, CA. As a math research assistant, Ross worked in the Advanced Development Projects group and studied how the P-38 Lightning, a fighter plane, responded to aerodynamic forces.

Ross took additional advanced classes at UCLA’s Extension School in aeronautical engineering and became a registered professional engineer in 1949, making her the first known Indigenous woman engineer!

She then transitioned to work at Lockheed Missiles and Space Company to work on projects like the Polaris missile, which is launched by a submarine. She also added to the Interplanetary Flight Handbook published by NASA in 1963,which explained the paths that spacecrafts would fly to reach Mars and Venus.

Although she retired in 1973, Ross continued to advocate for inclusion of women and Indigenous people in engineering, such as through the Los Angeles chapter of the Society of Women Engineers and the American Indian Science and Engineering Society.

Ross also supported the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian. Upon her passing in 2008, she bequeathed the museum over $400,000.

Read more about Mary Golda Ross here.

Further Reading:

Marie Tharp: https://marietharp.ldeo.columbia.edu/about-marie-tharp

Dr. Sudipta Sengupta: https://medium.com/sci-illustrate-stories/sudipta-sengupta-46f4a7ed441c

Zelma Maine Jackson: https://www.nwnewsnetwork.org/science-and-technology/2015-08-01/daughters-of-hanford-a-black-woman-geologist-digs-into-hanford-soil

Mary Golda Ross: https://airandspace.si.edu/stories/editorial/mary-g-ross-aerospace-engineer

Other works on the past contributions of women within geosciences:

Vincent, A. (2020) Reclaiming the memory of pioneer female geologists 1800–1929. Advances in Geosciences, 53, 129–154. https://doi.org/10.5194/adgeo-53-129-2020

Burr, D. M., S. Diniega, L.C. Quick, K. Gardner-Vandy, and F. Rivera-Hernandez (2022) Foundational women in planetary geomorphology: Some contributions in fluvial, aeolian, and (cryo)volcanic subdisciplines. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms, doi:10.1002/esp.5465. doi:10.1002/esp.5465

Hulbe, C.L., Wang, W. & Ommanney, S. (2010) Women in glaciology, a historical perspective. Journal of Glaciology, 56(200), 944–964. doi:10.3189/002214311796406202. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-glaciology/article/women-in-glaciology-a-historical-perspective/205304CE84CEFFCC59FA4BC83AB962AE

Fitzsimmons, K., McLaren, S. & Smalley, I. (2018) The first loess map and related topics:Contributions by twenty significant women loess scholars. Open Geosciences, 10, 311–322. https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/geo-2018-0024/html

Sack, D. (2004) Experiences and viewpoints of selected women geomorphologists from the mid-20th century. Physical Geography, 25(5), 438–452. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.2747/0272-3646.25.5.438?src=getftr&journalCode=tphy20