A Narrative of Louis Zachos's Search for the Devil's Eye

It’s an early February morning, cool but clear. A lone fisherman is sitting on an overturned 5- gallon bucket, holding a rod and watching two more on the bank beside him, all three lines in the river. I back carefully down the steep concrete ramp, feeling like an intruder. He offers to help me get the kayak off the roof rack. I must look older than I feel, because everywhere on this river people want to help me load, unload or carry the boat. It’s going to be a good day. The temperature is warming, and should be in the high 60’s later on. The river is low and flowing slowly, clear enough to see 2 or 3 feet to the bottom. The fisherman’s attention is distracted by a catch, a nice bass, and he unhooks it and tosses it in the grass. I wish him well, and he tells me that he knows he isn’t sup- posed to have a fire, but it was cold at dawn. I tell him it’s fine – there’s nobody around and there’s no grass or litter on the bank to burn anyway. I stock the kayak with all the essentials, wade into the water and push off.

Figure 1: A turtle takes advantage of

the imbricated tires.

I begin today from a Travis County park, located on the north side of the Colorado River, just east of Webberville, and just west of the Travis/Bastrop County line. In some ways it’s a ratty part of the river. Construction companies mine sand and gravel from the big bends of the river between here and Austin, although they are careful, for the most part, to isolate the mining from the river itself to minimize any muddying (or maybe they’re just law-abiding). It’s romantic to dream of mining gold or diamonds, but around here there’s money in dirt. Across the river from the park, and along the south side for maybe a mile upriver, the scenery consists of the backsides of a line of trailers and what can only be described as junkyards – old boats, concrete, rotting logs, plastic, and just plain trash. But downstream is where the Lower Colorado begins for me.

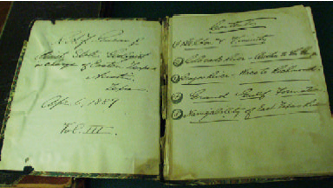

Figure 2: The field book of R.A.F. Penrose

covering the Colorado River trip of 1889.

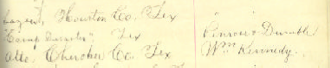

Figure 3: An entry for “Camp Disaster” in the

Species Register.

In 1889, three geologists of the fledgling Geological Survey of Texas came this way. The young R.A.F. Penrose, fresh with a doctorate from Harvard, E.T. Dumble, and R.T. Hill. The trio started out in a boat with a rower, but lost him and R.T. Hill a little downstream of here, at a place Penrose labeled “Camp Disaster” in his field notes.

There is no “Camp Disaster” on any map or in any other historic record – but I’m pretty sure it’s located somewhere near the mouth of Dry Creek. Some places are just plain unlucky, and here I’ve dropped my expensive Nikon in the river (twice!), a friend of mine sprained his ankle, and I cannot think of any place with a thicker growth of poison ivy. Noah Smithwick described overturning a dugout canoe near here in 1836 during the Texas Revolution. There is long stretch of shallow water along the right bank here – clays of the Paleocene Kincaid Formation – in places filled with all kinds of fossils The Paleocene is the earliest epoch in the Tertiary stretching from 65- 55 mya. The Kincaid Formation is part of the Midway Group, rocks from sediments that were deposited during the Paleocene. This clay falls apart on drying, so nothing can be seen along the banks above water and all the best collecting is had standing knee-deep in the river and scooping fossils like a heron bobbing for fish.

It’s only another sixteen miles or so to the next take-out point (under the bridge at Utley), an easy paddle/drift. Wilcox beds are cut by the river between Dry Creek and the Utley bridge. Unlike the Kincaid, which was deposited when the sea extended past here, the Wilcox was deposited by rivers and streams flowing across a widening coastal plain. In bluffs rising above Wilbarger Bend there are even beds of lignite exposed – remnants of ancient swamps. A little north of here Alcoa mines thousands of tons of Wilcox lignite to fire the generators that power the smelters that crank out the cans that contain the beer I drink as I drift with the current.

Figure 4: An early morning dip

from a sandy shore.

The gravel bars have now changed appearance as well. The cobbles of granite and worn shells of Cretaceous oysters have given way somewhat to petrified wood and flint. The Colorado River erodes and transports those eroded materials further downstream. Thus at any particular point in the river channel some of the constituents of gravel bars may be older than the rocks through which the river is flowing. Here we are finding older Cretaceous marine fossils and even older granites in the gravel bars when the river banks may be cut through younger Tertiary non-marine deposits. I imagine that the Indians selected blanks for their spear points and arrowheads from among these cobbles. Often a piece of flint looks as if it had worked by hand, perhaps a core from which broad flakes of stone were struck, or a cast off blank with a defect too subtle for my eye.

From Utley to Bastrop the river flows through a flood plain populated mostly by cows.

The Wilcox sands and clays are exposed here and there, spectacularly at one point with a vertical cliff of sandstone 40 feet high. William McKinstry passed this way in August, 1839, noting the ferry at Bastrop as well as shoals “familiarly known as the old San Antonio crossing” – old in 1839! The modern history of Bastrop County goes back to the original settlement of the Stephen F. Austin Colony, when Bastrop was named Mina.. It was only three years before, in March of 1836, that the “Runaway Scrape” streamed up the San Antonio Road through Bastrop as the Anglo populace evacuated Texas before the onslaught of Santa Anna’s army.

Below Bastrop, the Colorado River flows for some distance through the lignite-bearing Wilcox deposits. After a while, the left side of the river rises into tall, pine-covered hills, part of the Lost Pines region. The Lost Pines is a 70 square mile region of loblolly pine trees that were part of a continuous stretch of forest from here to East Texas during the Pleistocene. Now isolated from the eastern woods, they mark a change in the geology from the clayey Wilcox to the sandy Carrizo Formation and Newby member of the Reklaw Formation. A golf course hugs the north bank of the river, adding the hazard of a nasty slice to the other hazards of water moccasins and snapping turtles. The tall hills become cliffs framing the fairways, capped by rust-stained conglomerates. These high terrace deposits are very different from the thick red alluvium I’ve been seeing in the banks upriver. What could have washed such a thick mass of cobbles and pebbles over the land here? These cliffs have been known since before 1840 as Iron Banks and Red Bluffs, and have been a landmark along this stretch of river. Now, with the modern improvements of golf courses and expensive houses, it has been given the improbable name of Tahitian Village.

At the mouth of Cedar Creek there is a tall bluff of brilliantly white, cross-bedded sandstone of the Carrizo Formation, also capped by a few feet of iron-red pebble conglomerate. The clean, white sand of the Carizzo is replaced a little farther on by the red-colored sands of the Newby, the lower member of the Reklaw Formation. The red coloration is caused by the oxidation of the iron- bearing mineral glauconite. Glauconite, although its exact mode of formation is still unknown, is evidence of marine waters. The sediments here, after many miles of river, were once again deposited by the sea during the great inundation of the Claiborne. Also, after many miles, I once again find fossil shells.

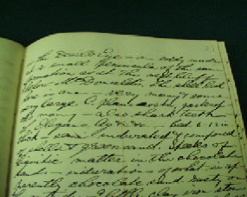

Figure 5: Penrose’s notes on

Devil’s Eye.

F.B. Plummer, in the Geology of Texas, stated “The first fossils from the Reklaw were named by Heilprin (1890) from a collection of fossils sent him by R.A.F. Penrose, Jr., collected from Devil’s Eye, a shoal in Colorado River about 8 miles southeast of Bastrop in Bastrop County.” Fisher, Rodda, and Dietrich (1964) describe Devil’s Eye as an “... island in Colorado River”, and Garvie (1996) as “...former island in Colorado River.” At least they seem to agree that it is some- where between David Bottom and Kennedy Bluff. Unfortunately, no one seems to agree on where, exactly, David Bottom is located. David Bottom was one of five communities created in 1828 by seven Missouri families among the original settlers of the S.F. Austin grant. It was probably located along the north side of the river below Cedar Creek, although some current residents of the area place it five or six miles farther downriver.

Figure 6: A contender for Devil’s Eye?

The stranded boat wrapped around

the cottonwood tree indicates times

of much higher water.

In the Colorado Navigator (1840), William McKinstry gave a detailed description of the Colorado River between Austin and the Gulf of Mexico, based on a trip by small boat. In this record we find what may be the earliest reference to Devil’s Eye – an island in the river, between Bastrop and Smithville, called Devil’s Towhead. The Random House Dictionary of the English Language defines towhead: a sand bar in a river, esp. a sand bar with a stand of cottonwood trees.

But now we come to another problem with his description of the river – the mileages don’t add up to modern distances. This was admitted by McKinstry himself in the preface to his publica- tion: “The distances between the different points and towns ... may possibly differ a little ...”. The same problem is found in the field log of R.A.F. Penrose in his description of a trip down the Colo- rado from Austin to LaGrange. Fortunately, we can recognize some of the other landmarks noted, and thus gauge the actual distances between other points of interest.

McKinstry gives the mouth of Walnut Creek as a station. Now called Cedar Creek, this point almost certainly coincides with the present day location.

- Total distance of 7.75 miles given between Walnut Creek and Devil’s Towhead.

- Total distance of 8 miles to Burleson’s Ferry.

- Total distance of 3.25 miles to Gazly’s Landing (Smithville).

- This gives a total from Walnut Creek to Smithville of 19 miles.

- The same measured from a modern map is 12.7 miles.

There is a significant discrepancy in the measurements (12.7 miles vs.19 miles, or 2:3). If this factor is applied to each incremental measure the following distances would be expected:

- Walnut Creek to Devil’s Towhead – 5.2 miles

- Devil’s Towhead to Burleson’s Ferry – 5.35 miles

- Burleson’s Ferry to Gazly’s [sic] Landing – 2.2 miles

Penrose also gives the mouth of Walnut Creek as a station. By his measurements, Devil’s Eye is 5.5 miles from the mouth of Walnut Creek. McKinstry noted that Devil’s Towhead was about a 1⁄4 mile long. Assuming that Devil’s Eye was at the downstream end of the island, the two measurements are in close agreement.

Figure 7: Beached on Devil’s Eye Shoal

In the First Annual Report of the Geological Survey of Texas, Penrose states that “Four miles below the beginning of this fossiliferous area we come to what is locally known as the Devil’s Eye, an eddy at a low ledge ...”. In Penrose’s handwritten field notes we have even more information: “2 miles below McDonalds Bluff is the Devil’s Eye – an eddy made at a small peninsula of the same formation as at the next bluff below McDonald’s.” Just upstream of this eddy he describes “many shells in the blocks of indurated greensand in the river – small shoal – dip horizontal...”

Figure 8: Typical fossil material

preserved in the Non-vertebrate

collections of the Texas

Memorial Museum.

Figure 9: Fossil leaves at a Yegua

outcrop along the Colorado

River in Fayette County.

The river makes a sharp bend where Reeds Creek enters from the south, and a tall bluff on the south bank exposes nearly forty feet of the Marquez member of the Reklaw – this is McDonalds Bluff. About a mile below the bluff the river bends northward again. At high water the channel splits, flowing around an island about a quarter mile in length and dotted with cottonwood trees. At low water, the left channel is a long stretch of sand, and a ledge of glauconitic sandstone forms a small set of falls entirely across the remaining channel. The sandy clay underneath is filled with fossil shells of the Reklaw.

From an aerial photograph it is apparent that the ledge marks a fault that crosses the river here. An aerial photograph from 1951 shows not only the ledge, but the extension of the fault where it again crosses the river past an eastward bend about a quarter mile downstream. The left bank here is partly eroded away by what appears to be a strong eddy. At the present time, however, the eroded section is slumped and densely overgrown. Some other time I am going to stop with shovel and pick and see if I can find any fossils to confirm that this is the missing Devil’s Eye.

The thick, massive Queen City sand above the Reklaw forms a long line of bluffs along the right bank for a mile or so above Alum Creek, and one of the more spectacular bluffs just below the mouth – a sixty foot cliff of sandstone and shale named Kennedy Bluff. Penrose stated that the same shell bed found at Devil’s Eye is present above twenty feet of cross-bedded sandstone, and the TMM collections have fossils reported to be from Alum Creek Bluff. But this is another mystery. I can’t find any fossils on this cliff, and it is difficult to explain how a Reklaw section could appear within the Queen City. Besides, Penrose, in his handwritten notes, locates the bluff on the south side of Alum Creek. Kennedy Bluff is on the north side of Alum Creek.

Figure 10: Pump station near Kirtley.

Water from the Colorado is still

pumped for stock and crop irrigation.

Figure 11: Further downstream the

bluffs of Yegua shales near the bend

in the Colorado, site of the fossil

leaves shown in Figure 9.

About two miles below Alum Creek, on the left (north) bank, is an exposure of Queen City sandstone. At low water levels a bed of fossiliferous greensand can be seen just below the surface. Amongst the shells I find many shark teeth. This locality was not known to Penrose, or any writers after him, but one local fisherman told me “I found some shark’s teeth around there.” Penrose also did not note the fossiliferous Queen City bed at the mouth of Gazely Creek, but it was described by Price and Palmer in 1928.

This trip ends at the LCRA boat ramp under the State Highway 95 bridge in Smithville, but not before drifting a few hundreds yards further down to the ledge of oyster-bearing “limestone” extend- ing nearly across the channel. The houses and manicured lawns on the right bank cover one of the classic collecting localities of the Texas Tertiary section. Paleontologists collected from the well- exposed Weches greensand for more than 50 years before the bank was stabilized by flood control and urban growth. The original wagon bridge, built around 1900, crossed downstream of the expo- sure, which was described in detail by H.B. Stenzel. There are no other comparable Weches outcrops within a hundred miles, and our knowledge is almost entirely dependent upon museum collections (and what little can be gleaned from the rock ledge today).

The records continue past the town of Smithville, this leg of the original survey ended in La Grange.