Active Sulfidic Cave Systems

Of all the known caves in the world, very few formed from sulfuric acid speleogenesis, and even fewer are actually forming today by this process. While these caves are themselves quite interesting phenomena from a geological standpoint, these systems also have many different microhabitats occupied by a wide variety of microorganisms. In general, the composition of microbial communities in the caves is controlled by the chemistry of the groundwater, the sources and types of reduced sulfur compounds and other essential nutrients, as well as the mineralogy of the host bedrock. The following examples are from some of the known and well-characterized sulfidic cave systems.

Movile Cave, Romania

Airbell in Movile Cave, Romania, with floating mats and wall mats. The PVC pipes are 10 cm on a side. (1998 photo)

Movile Cave is located approximately 3 km from the Black Sea coast in Southern Dobrogea. The cave has 200 m of dry passages, and ~40 m of submerged passages and airbells (shown here is an airbell). The cave and its strange ecosystem were discovered in 1986, although sulfidic springs have been known from the region since the Roman times. To date there are about 30+ new species of terrestial and aquatic animals that have been found in the Movile Cave and surrounding sulfidic groundwater system. The ecosystem was the first suggested terrestrial system based chemosynthesis, similar to the deep sea hydrothermal vents (Sarbu et al. 1996). The chemosynthetic microorganisms can be found in the lower part of the cave, in one of three types of microbial mats. Here are the wall and floating mats. A submerged mat (not shown) covers rock and sediment surfaces at the bottom of the water column. Below several millimeters in the mats, the water becomes anoxic, and consequently the submerged mat consists of mostly anaerobes, especially methanogens. The wall mat consists of predominately fungi, but there are sulfur-oxidizers and other bacteria found, as well as moist organic material adhered to the rock surface, about 2-3 cm thick in places. The floating mat is quite unique to the cave. This mat is a complex microbial habitat, comprised of fungal hypae and an assortment of bacteria. The mat is very thin (like wet tissue paper) and is kept afloat due to air bubbles.

For more information: Movile Cave Project – compiled by Romanian researchers Karst Water’s Institute 2nd Annual Top Ten List of Endangered Karst Systems

Cesspool Cave, Virginia

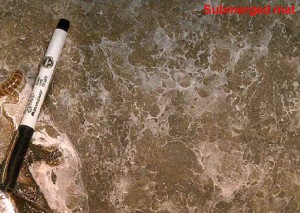

Thin, delicate filamentous mats in Cesspool Cave, Virginia, consisting of predominately sulfur-oxidizing bacteria such as Thiovulum and Thiothrix. Sediment surface is approximately 10-15 cm deep. Left of the pen is a centipede and leaf litter. (photo by Megan Porter, 1998)

Cesspool Cave is located in Allegheny County, Virginia, near the West Virginia border. The cave is developed in travertine, formed as a result of travertine-depositing streams common to the area. The cave only has 20 m of passage so there is only total darkness at the farthest points in the cave. Hubbard et al. (1990) reported the presence of sulfur-oxidizing bacteria in the cave, and suggested that these microbes were responsible for cave formation through the generation of sulfuric acid. Webs of microbial mat float on the sediment surfaces with organic material that gets washed into the cave. Porter (1999) found that the predominate microorgniams are chemoautotrophs based on primary productivity measurements. While thiobacilli were most commonly observed microscopically, molecular genetic data suggest that most of the microbes are Thiothrix spp. and Thiovulum spp. 16S rDNA gene sequences of pure cultures of sulfur-oxidzing bacteria reveal the presence of Thiomonas thermosulfatus (syn. Thiobacillus thermosulfata) (Engel et al., 2001).

Frasassi Caves (Grotto Grande Del Vento – Grotta Del Fiume System), Italy

Microbial draperies, or "snottites", in Grotta del Fiume, Italy, associated with elemental sulfur, iron oxide crusts, and gypsum. (photo by Annette Summers Engel, 1998)

The Frasassi Caves have been studied extensively by Italian speleologists, and Galdenzi (1990) proposed that the system was formed from sulfuric acid corrosion due to the active sulfidic stream that flows through portions of the Grotta del Fiume cave, and abundant gypsum and sulfur accumulations throughout the entire cave system. Where the cave passages intercept the sulfur stream, there is a range of microbial mats. On the cave walls, sulfur and gypsum crystals grow on and through a thick paste of milky gypsum and corroded limestone. Microbial draperies (the consistancy of mucous) hang from crystals and wall protrusions, where some droplets are about 5 cm in length. The average is 2 cm long, however. Acid droplets form at the tips of the draperies and have a pH of 0 to 1 (Vlasceanu et al. 2000). The microbial community is dominated by acidophilic, sulfur-oxidizers, especially Thiobacillus spp. Microbes are not restricted to the wall surfaces, as there are thick filamentous mats in the stream passages.For more information: The Frasassi Caves Federation, Genga, Italy

Lower Kane Cave, Wyoming

Sampling water in Lower Kane Cave, Wyoming. White area in front of Megan Porteris thick filamentous white microbial mats. (photo by Annette Summers Engel, 2000)

Lower Kane Cave is part of a multi-cave system that formed by sulfuric acid speleogenesis along the Bighorn River in north-central Wyoming. While Lower Kane Cave has several hydrogen sulfide-rich springs that discharge into the passages, several caves in the area are no longer active but retain some indications of having formed through sulfuric acid dissolution. The caves were studied by Egemeier (1981), who found that oxidation of H2S to sulfuric acid contributed to karstification by a “replacement-solution” mechanism. However, this process was thought of as strictly abiotic, and that sulfur-oxidizing microorganisms were not considered major players in the speleogenesis process. More recent investigations in Lower Kane Cave and others indicate that diverse microbial populations proliferate the caves, forming dense microbial mats and biofilms in both aqueous and subaerial settings. Lower Kane and others are currently being investigated. (Photo by Annette Summers Engel, 2000)For more information: Lower Kane Cave Project, maintained by University of Texas at Austin, Geomicrobiology Research Group Abstracts from the UT-Austin Group

Cueva De Villa Luz, Mexico

Snottites in Cueva de Villa Luz. Image by Jim Pisarowicz, from 1998 Field trip website.

Cueva de Villa Luz, or the “Cave of the Sulfur-Eaters”, is located in Tabasco, Mexico, and has received quite a bit of media attention over the years. This exciting cave is full of stinky sulfide springs and microbial draperies reaching nearly 0.5 m in length. Like reported from other sulfidic caves, these snottites have acid drops at their tips, with a pH ~ 0, and are associated with gypsum and elemental sulfur deposits. The cave systems is currently being investigated by a large group of researchers at various institutions (Hose et al. 2000). For more information: Biological Investigations in Cueva de Villa Luz, multiple investigators’ findings 1998 Field trip website

Some other sulfidic (active and ancient) cave systems

- Lechuguilla Cave (site about cave microbiology, by Diana Northup and others), Lechugullia Cave links

- Carlsbad Caverns, New Mexico (National Parks Site)

- Cupp-Coutunn Cave, Turkmenistan (mostly images) and informative article regarding cave’s geology and mineralogy, both by Vladimir Maltsev