Discussion

Platinum-group Element Detection

The main goal of this project was to determine if 1) different minerals (i.e., pentlandite and phlogopite) that are associated could be correlated with their PGE contents, and 2) if the PGE and associated trace element contents (e.g., Se and Te) could be used to discriminate between the physical parts of the pipe (i.e., the rim of the pipe and the core of the pipe) using pentlandite (representing the sulfide melt) and/or phlogopite (representing the metasomatic fluid). Previous studies have determined that the sulfides (pentlandite) and the phlogopite represent the infiltration of a metasomatic fluid into the cooling peridotite pipe body (Garuti et al., 2001; Fiorentini et al., 2002; Fiorentini and Beresford, 2008; Locmelis et al., 2016, 2021), and therefore are genetically related and co-crystallized from the same fluid.

While it is known that in general, PGE do not preferentially fractionate into the silicate fluid/melt when there is a sulfide component present, the phlogopite in association with sulfides have never been analyzed for PGE. However, it was determined that the PGE contents in phlogopite were overwhelmingly below detection limits (Results, Table 2), likely due to a low fractionation of PGE into the fluid phase (e.g., H2O-CO2-rich volatile silicate fluid). The initial goal of this project was to try to use PGE in phlogopite as a proxy for the metasomatic fluid, however, with the low to non-existent PGE concentrations in the phlogopite measured, the research goal evolved into using the present Ni-Cu-PGE contents of both pentlandite and phlogopite as physical discriminators between the pipes themselves, and between the rim and core of the pipes.

Rim vs Core?

One of the new research questions being asked is: Can we use the PGE and associated trace element contents (e.g., Se and Te) in order to discriminate between the physical parts of the pipe (i.e., the rim of the pipe and the core of the pipe)? This is a critical question, as the Valmaggia pipe is characterized by higher sulfide contents in the pipe rim, however, numerous other pipes are no longer accessible via their mine workings to see their physical relationships, restricting observation to tailings piles. In previous studies, it was determined that the rim of the pipes are more sulfide-rich because the rim contact of the pipe acted as a weak point that became a conduit for metasomatic fluid flow (Garuti et al., 2001; Fiorentini et al., 2002; Fiorentini and Beresford, 2008; Locmelis et al., 2016, 2021).

Samples VMG-I6A and VMG7 are from the rim and core (respectively) of the Valmaggia pipe. However, the mine workings at the Fei di Doccio pipe have collapsed completely, leading to the original pipe geometry being obscured. In terms of exploration, it is critical to be able to identify where the samples of higher metal (i.e., Ni, Cu, PGE) contents are coming from in order to guide exploration and understand the fluid flow, fluid-rock interactions, and the associated ore-forming processes.

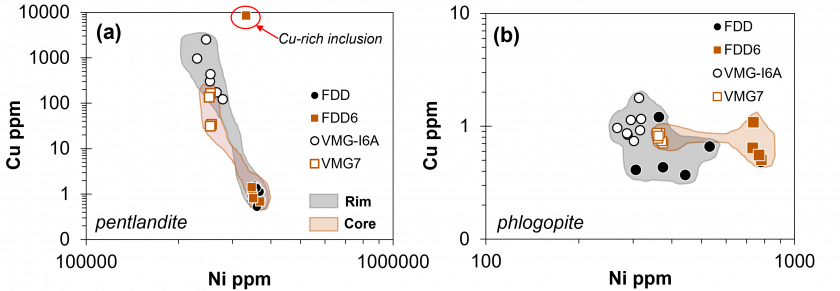

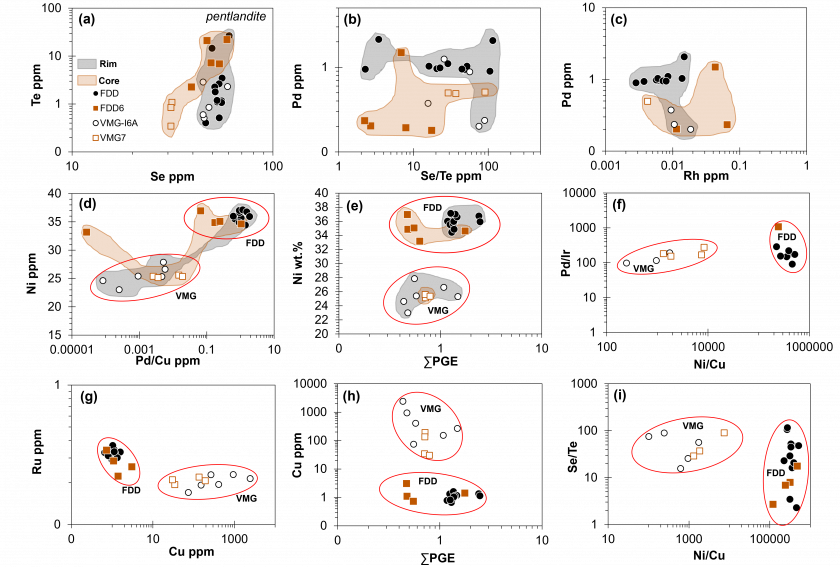

While the sulfide Ni vs Cu contents (Fig. 1) were inconclusive for discrimination between the possible rim and core domains of the pipes, the Ni vs Cu shows a clear distinction between not only the individual pipes themselves (i.e., Valmaggia pipe and the Fei di Doccio pipe), but additionally discriminated between the rim and the core of each pipe (Fig. 1).The phlogopite Ni vs Cu (Fig. 1) contents show promise as a physical tracer/discriminator to identify different metasomatized zones in these pipe systems. It was found that by using various binary discrimination diagrams for pentlandite, the chemical difference between not only the pipes themselves was obvious, but the rim and the core of the same pipe can be differentiated (Fig. 2). Figures 2a-e show varying chemical discrimination between the rim and core domains of both pipes, while Figures 2d-i show clear discrimination between the Valmaggia and Fei di Doccio pipes. These results indicate that PGE+Ni-Cu-Se-Te compositions in pentlandite have potential to be used as physical discriminators of where the ore is coming from (highly metasomatized rim vs poorly metasomatized core).

Discussion of Error

The recovery of PGE was quite low for all samples. Several factors, including an actual lack of PGE present, contributed to values being below detection limits. Inevitable sources of error were the size and quality of crystals ablated. While every effort was made to select large clean crystals, in order to have a statistically significant number of samples some smaller and more cracked or included crystals were included in the final sample list. In short, we were limited by the physical constraints of the samples themselves. Additionally, the heterogeneity of Fe in phlogopite sets off the internal standard of Fe, thereby propagating error across the sample data.

A secondary source of error has to do with sample preparation. Our method (relatively low fluence, 7 µm drill depth) should have theoretically ensured that the laser would not reach the glass on the back of thin sections. However, a majority of the phlogopite grains were completely ablated by the laser, which continued to drill into the glass. This is not fully explained by the composition of the phlogopites themselves, and likely means that our thin sections were anomalously thin. The standard thickness of a thin section is 20 µm so regardless of the composition of the sample, the laser should not have reached glass based on drill depth. Future work may benefit from analysis of samples in the form of epoxy mounts which may lend themselves to greater crystal volume. Additionally, recovery of ablated material may be improved by lower repetition rate (<10 Hz) or lower fluence (<2.8 J/cm2). A SQUID device may be used to smooth pulse disturbance, ensuring a consistent level of input to the plasma. LA-ICP-MS methods suffer from noise interferences caused by the nature of ablation itself; attention to the method of particle delivery to plasma may improve overall signal quality and thereby data accuracy and precision.

Otherwise, the recovery and relative error for internal standards and reference standards was quite good. The near perfect precision of recovery for the UQAC-Fes-1 standard supports the validity of our method, especially for sulfide-rich samples. This project supports future work concerning LA-ICP-MS analysis of magmatic sulfides as this method produced relatively precise data for a genetically difficult set of samples. Further improvements to this method would include precise standardization of thin sections for all samples and perhaps a greater sample size which may increase overall measures of accuracy. Methodological changes including variations in repetition rate, fluence, and instrument mechanics may additionally improve recovery of sample.

Final Cost

The final cost for this project was $845, accounting for approximately 13 hours of time spent to set up the method, run the analysis, and process data. This relative increase in cost from the budget put forth in the proposal reflects additional time spent learning the machine and software in order to accurately set up our method. Actual run time was about 3 hours, representing only about a quarter of the final cost.