Mammal Forerunner— and 38 Babies— Shed Light on Brain Evolution

December 3, 2018

A newly described fossil of an extinct mammal relative — and her 38 babies— is among the best evidence that a key development in the evolution of mammals was trading brood power for brain power.

The find is the only known fossils of babies from any mammal precursor, said researchers from The University of Texas at Austin who discovered and studied the fossilized family. The presence of so many babies — more than twice the average litter size of any living mammal — revealed that it reproduced in a manner akin to reptiles.

The study, published in the journal Nature on Aug. 29, 2018, describes

specimens that researchers say may help reveal how mammals evolved a different approach to reproduction than their ancestors.

“They had a lot of features similar to modern mammals, features that are relevant in understanding mammalian evolution,” said Eva Hoffman, who led research on the fossil as a graduate student at the Jackson School of Geosciences.

Hoffman co-authored the study with her graduate advisor, Jackson School Professor Timothy Rowe.

The mammal relative belonged to an extinct species of beagle-size planteaters called Kayentatherium wellesi that lived about 185 million years ago. When Rowe collected the fossil more than 18 years ago from a rock formation in Arizona, he thought that he had found a single specimen. Sebastian Egberts, a former graduate student and fossil preparator at the Jackson School, spotted the first sign of the babies in 2009 when he noticed a speck of tooth enamel as he was unpacking the fossil.

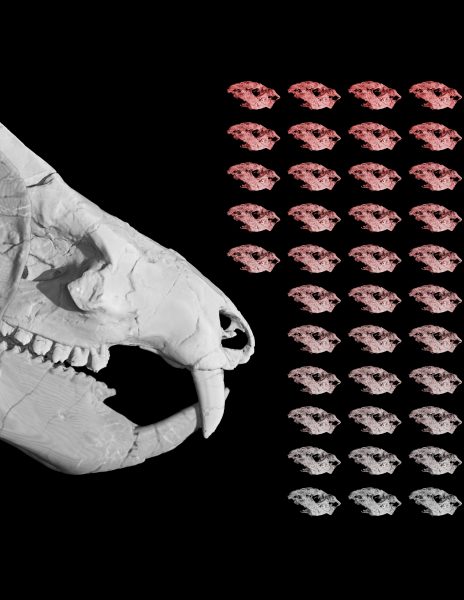

A CT scan of the fossil revealed a handful of bones inside the rock. However, it took advances in CT-imaging technology during the next seven years to reveal the rest of the babies.

Visualizations produced by Hoffman revealed that the skulls of the babies were like scaled-down replicas of the adult. This finding is in contrast to mammals, which have babies that are born with shortened faces and bulbous heads to account for big brains. The discovery that Kayentatherium had a tiny brain and many babies, despite otherwise having much in common with mammals, suggests that a critical step in the evolution of mammals was trading big litters for big brains and that this step happened later in mammalian evolution.

Back to the Newsletter