TexNet: Getting to the Bottom of What’s Causing Quakes in Texas

October 14, 2016

By Anton Caputo

Alexandros Savvaidis had never been to Texas before starting his new position at the Bureau of Economic Geology. Since arriving in January 2016 though, the native Greek has become very familiar with the large expanse of land within the state’s borders.

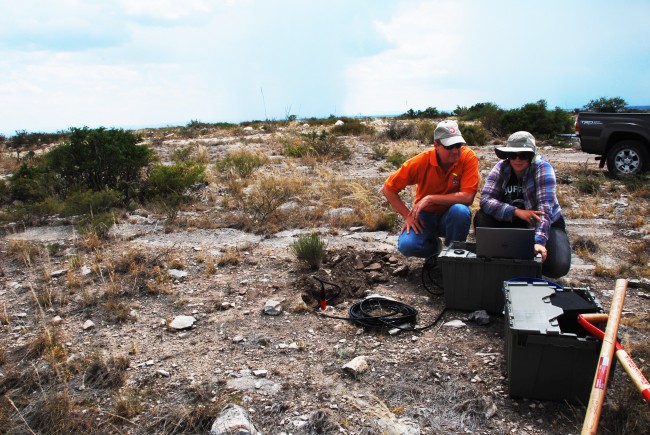

Savvaidis is leading the deployment of the TexNet seismic network, a job that has him and his colleagues crisscrossing the state, visiting and testing potential sites for the most comprehensive state-run network in the country.

TexNet, which will begin operating at the end of 2016, is the backbone of the state’s far-reaching approach to gathering information about subsurface seismic activity throughout Texas and answering a difficult question plaguing many oil-producing areas across the country — how are some fluid disposal wells used by the industry causing low-level earthquakes?

Savvaidis, who is TexNet project manager, has made a career of operating similar seismic systems in Greece and other parts of Europe. He said that the opportunity to build a system nearly from scratch was too good to pass up. Laying the groundwork has been challenging given the size of the state, but he’s confident the work will pay off soon.

“This has been a big issue for us. The state is big. The ranches are big,”he said.”What is important from our side is that we work proactively in the state in order to provide the necessary information to protect the public and the industrial infrastructure.”

At issue is how a small subset of wells commonly used to dispose of wastewater from hydraulic fracturing and water co-produced with oil and gas could be triggering faults. Mounting yet circumstantial evidence points to a link between disposing of fluids by injecting them deep into the ground and earthquakes, but comprehensive data is not available. The lack of data, coupled with the complexity of the science, makes definitive answers impossible at the current time.

“Trying to understand what actually caused a fault to move is not simple science,” said Scott Tinker, director of the Bureau of Economic Geology, who led the formation of TexNet with the state. “It involves the time of the event and the position both on a map and at depth. It also involves how the fault system is oriented in today’s stress fields as well as local and regional tectonics. And it involves changes in the earth system from the disposed fluids.”

The goal of TexNet is to cut through the speculation by collecting the sorely needed data straight from the source.

LONESTAR LEADERSHIP

Texas Gov. Greg Abbott and the legislature in June 2015 authorized $4.47 million for TexNet and related research—both initiatives led by the bureau, which also serves as the State Geologic Survey of Texas. Since then, researchers have quietly gone about the business of building the system from the ground up — or down, with Savvaidis and others traveling the state to identify and survey potential sites and negotiate leases for the locations of the seismic sensing stations with landowners. A good spot for a seismometer is quiet and solid, Savvaidis said. Background noise and loose rock or soil can interfere with the sensors.

“We try to avoid unconsolidated formations,” Savvaidis explained. “We try to find more stiff formations like the Cretaceous limestones we have in abundance here in the state of Texas. We can do this anywhere, but we would prefer to have stiff soil and rocks because usually the noise level is really low.”

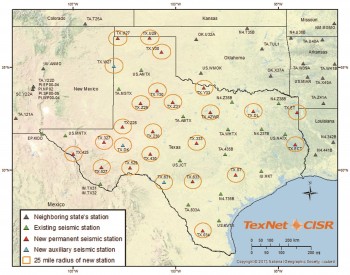

TexNet is being built around an ad-hoc system of seismometers already in place — 17 seismic stations throughout the state run by the U.S. Geological Survey and Southern Methodist University. TexNet will add 22 more permanent stations and another 36 portable seismometers, each with sensitive accelerometers, in key areas around the state to test various scientific hypotheses. Once in place, the stations will continuously monitor the sites for seismic activity, with data eventually being streamed live to the system’s website where anyone can view it.

“This is a vital topic that spans a huge base of stakeholders including the public, cities and municipalities, the petroleum industry and their need and desire for sustainable business practices, the state of Texas and the regulators, and then, of course, a broad base of academic specialties,” said Peter Hennings, a research scientist at the bureau and a principal investigator in the bureau’s Center for Integrated Seismicity Research. Monitoring is only part of the equation. The state funding and directive that formed TexNet motivated the creation of the Center for Integrated Seismicity Research (CISR), a multidisciplinary research group that will work in parallel with TexNet to conduct fundamental research to better understand natural and induced earthquakes in Texas.

The role of TexNet is not to make policy decisions, explained Robie Vaughn, chair of the Technical Advisory Committee appointed by the governor to help guide the project, but to provide technical and scientific information to assist policy and decision makers.

“Our job is to focus on the science and provide the governor and the legislature with the data and the hard facts,” Vaughn said. “I really believe Texas is leading by investing in a disciplined process to best understand the issue.”

RESEARCH RENAISSANCE

Over the past several years, researchers in Texas and throughout the country have become increasingly interested in the question of whether oil and gas activity can cause earthquakes. That’s because, according to the U.S. Geological Survey, the annual occurrence of earthquakes of magnitude 3 or larger has increased significantly within the central and eastern United States since about 2009. These earthquakes are typically large enough to be felt, but usually small enough not to cause damage, although in Oklahoma the quakes have generally been stronger than those in other parts of the country.

In Texas, it was a series of quakes in the Dallas-Fort Worth area beginning in 2008 that started scientists to begin to investigate the link, said Cliff Frohlich, a seismologist with the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics. Frohlich, who is part of TexNet and CISR, said that in the early years induced seismicity was a niche interest, with only a small group of scientists looking into the issue.

But now seismicity research in Texas is in a “renaissance” of sorts when it comes to investigating earthquakes’ potential link to human activity, he said.

“For most of my career, induced earthquakes were a minor sideline — a minor unfunded sideline,” he said. “Now you go to a meeting and there will be four different sessions, and I’m one of 50 or 60 people speaking. When you have 50 people working on something, progress is being made.”

The early research, Frohlich said, was complicated by a hodgepodge system of seismometers, a lack of data, and even undefined roles and responsibilities. “I used to say I was the world’s leading authority on Texas earthquakes, but it’s not a paid job.” Frohlich quipped. “But with TexNet, a lot of these problems should improve.”

INTERDISCIPLINARY APPROACH

The new data from TexNet is just part of the data that CISR is collecting. Another important resource comes from industry partners (currently 10 and counting). Data that companies have collected over the years is crucial to the effort, Hennings said, because often it is the best, and sometimes only, information available on subsurface Texas in a given location.

The industry-research collaboration also extends to CISR’s principal investigators, who include oil and gas professionals, as well as researchers at universities across Texas. Hennings joined the CISR research team after spending 25 years in the oil and gas industry where he was a research scientist and technical manager. He said he’s never seen an effort as thorough as TexNet and CISR.

“In terms of subsurface geoscience application, I really don’t know of another project that has this type of interdisciplinary breadth,” Hennings said.

In addition to Hennings and Savvaidis, Ellen Rathje, a professor of civil engineering at The University of Texas Cockrell School of Engineering, is serving as co-principal investigator of CISR. At The University of Texas at Austin, the research collaboration spans the Bureau of Economic Geology, the Institute for Geophysics, the Department of Petroleum and Geosystems Engineering, the Department of Psychology and the Moody College of Communication.

TexNet also includes Southern Methodist University’s North Texas Seismicity Study Group—which Hennings and Frohlich described as a pioneer and leader in the field — and the Texas A&M Department of Petroleum Engineering. CISR also includes the Stanford Center for Induced and Triggered Seismicity.

The research the consortium will undertake is designed to understand the subsurface processes that may influence seismicity. The work will include the study of earthquake sequences, triggering analysis, fault characteristics, fault sensitivity, fluid data and more. There will also be research on infrastructure vulnerabilities throughout the state and strategies for best communicating the issues to the public.

The first project, which is already underway, is “an integrated assessment of the seismicity potential of the Fort Worth Basin and how it might relate to oil and gas operations,” according to CISR’s website. Future focus areas include the greater Permian Basin, especially the Delaware Basin where unconventional oil development is expected to accelerate in the coming years. The Eagle Ford play area, the East Texas Basin and Haynesville play area and the Texas Panhandle are also areas that will be focused on in the future.

Ultimately, it may take years for TexNet to meet its goal of providing the kind of science that will help decision makers determine the best approaches for avoiding or responding to seismicity in Texas. The current schedule calls for the Fort Worth Basin assessment to be complete by the end of 2018 and the Permian Basis assessment by the end of 2020, with the Eagle Ford and Panhandle assessments to follow.

Tinker said that part of the challenge is keeping a realistic perspective of the problem while the work is being done;it’s quite likely that some disposal wells have and are causing seismicity, he said, but there are nearly 8,000 such wells in Texas, and the vast majority have been used for years, if not decades, without issue.

“This is right at the heart of what I call the radical middle; where industry, government, academia and the public converge,” Tinker said. “Texas wants to have oil and gas produced in its state and fluids disposed safely. It’s good for commerce. It’s good for the economy. And a healthy economy is good for environmental investment. Part of the challenge is making sure that all the things that are done right — the vast majority — aren’t shut down in the process.”

Back to the Newsletter