Researcher Details Climate Consequences of “Regional” Nuclear War

August 8, 2008

You’ve probably heard the term nuclear winter. In the early 1980s, climate scientists using simple computer models discovered that a large scale nuclear war between the U.S. and Russia would do more than kill millions of people in those two countries. Recent studies have borne out the initial results: such a bombardment would produce smoke, aerosols and dust that would block out sunlight and lead to years of global cooling on the order of 8 degrees Celsius. This would be devastating to natural ecosystems and to the agricultural system we depend on for survival.

Alan Robock of Rutgers University, one of the early proponents of the nuclear winter theory, recently used a NASA climate model to investigate what the impacts would be of a more limited, regional nuclear war. The test example involved two hypothetical countries with medium-sized nuclear arsenals bombarding each other with a total of 100 missiles the size of the bombs dropped on Hiroshima in 1945.

Robock presented his findings to a group of professor Liang Yang’s students at the University of Texas at Austin this April.

The climate model predicted a rapid drop in average global temperature of about 1.25 degrees Celsius. Global precipitation would also drop by about nine percent within a couple of years. Reduced temperature and precipitation would continue for more than a decade.

“So it wouldn’t be a nuclear winter, but it would affect us and our agriculture,” said Robock.

The cooler temperatures would mean a shorter growing season as the last freeze happens later in the spring and the first frost begins earlier in the fall. At mid-latitudes, the growing season would be on the order of 10 to 30 days shorter, according to Robock’s simulations. Plants would also grow more slowly and yield less in a cooler world.

To add insult to injury, ozone depletion, which had been improving after the banning of CFCs in the 1990s would reverse course and strip away much of our natural protection from harmful UV radiation. There would also be radioactive fallout and toxic chemicals from the burning released into the soil, air and water.

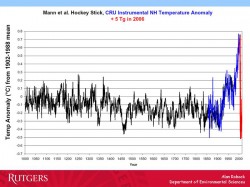

Robock showed the famous hockey stick graph (Mann et al., 1999), indicating global surface temperatures over the past thousand years. Then he tacked on ten years of temperature simulations following a regional nuclear war. The temperature drop of 1.25 degrees Celsius would bring global average temperatures below any recorded in the last millennium, even including the “Little Ice Age” which by some estimates occurred in the 15th through 19th centuries. And the chill down would happen within a couple of years, not decades or centuries, making adaption much more difficult than past changes humans have endured.

“Even a ‘small’ nuclear war between India and Pakistan, using much less than one percent of the world’s nuclear arsenal, would produce global climate change unprecedented in human history,” said Robock.

by Marc Airhart

For more information about the Jackson School contact J.B. Bird at jbird@jsg.utexas.edu, 512-232-9623.